The Phantom Reclamation Project That Just Won’t Die

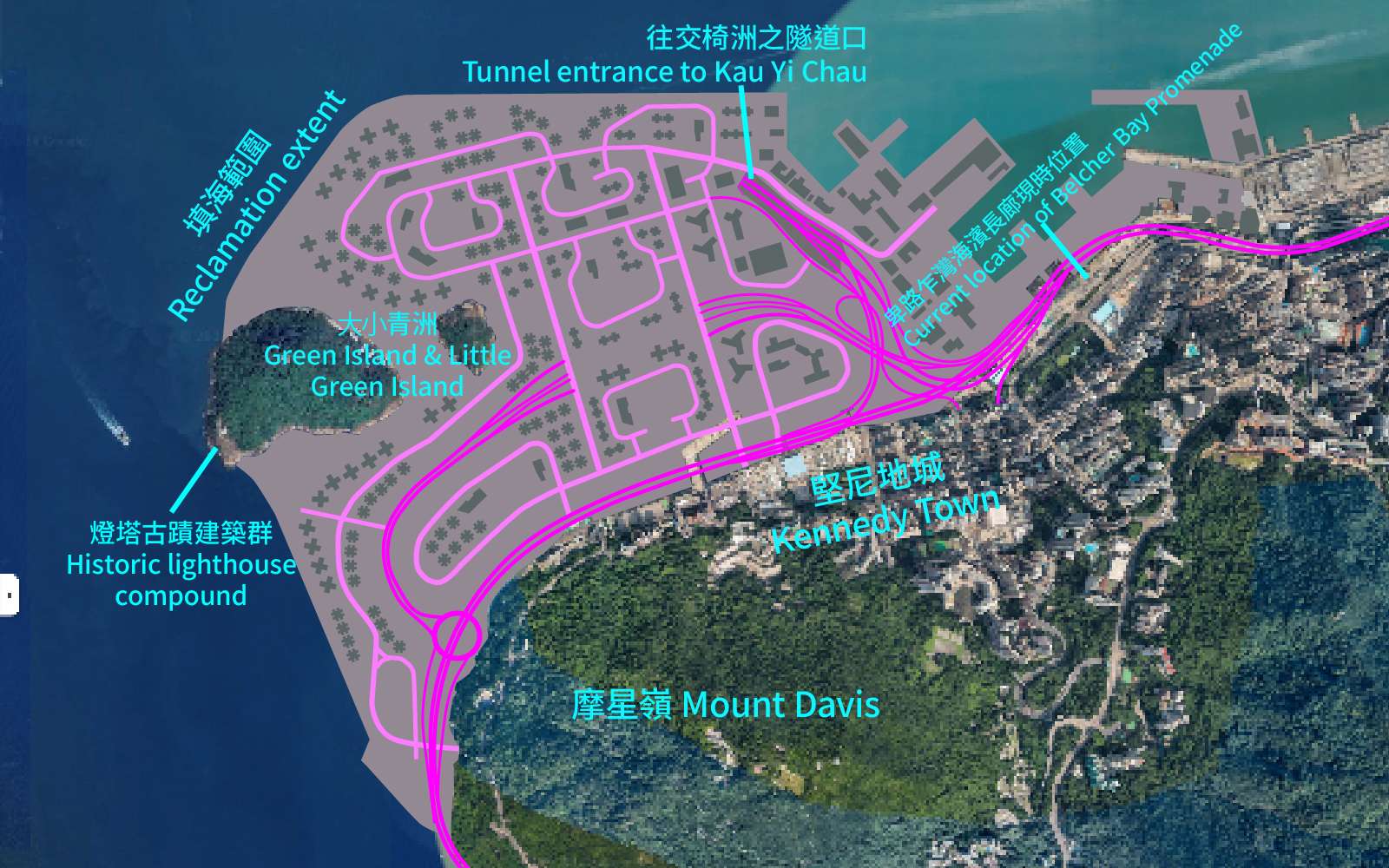

If you follow the Western Harbour Walk on the Hong Kong Island Coastal Trail, you will pass the Belcher Bay Promenade. This multi-use, pet-friendly space became a vibrant hang-out spot soon after it was completed in 2020. If you look out to sea here, you will notice two small islands on your left, Green Island and Little Green Island. They are off-limits to the public, as Green Island is home to one of Hong Kong’s oldest still operational lighthouses. However, if a project from the early 1990s had gone ahead, you would not be looking at the sea but at scores of apartment buildings and the entrance ramp of a tunnel to Lantau. You would be able to walk to Green Island, which would have been turned into a park.

This project belongs in a phantom city of unbuilt infrastructure that exists only in old planning documents and engineering studies, poorly digitized PDFs, and the dusty filing cabinets of government departments. And believe it or not, the unrealised plan to reclaim Green Island is connected, quite literally by tunnel, to the present day Kau Yi Chau Artificial Islands project.

Kau Yi Chau Version 1.0

Hong Kong has been talking about the Kau Yi Chau Artificial Islands project for ten years now, though nothing has yet been built. However, the idea of reclaiming the waters around Kau Yi Chau, a small island in the middle of the sea between Hong Kong Island, Lamma, and Lantau, is much older. It dates back to the 1980s.

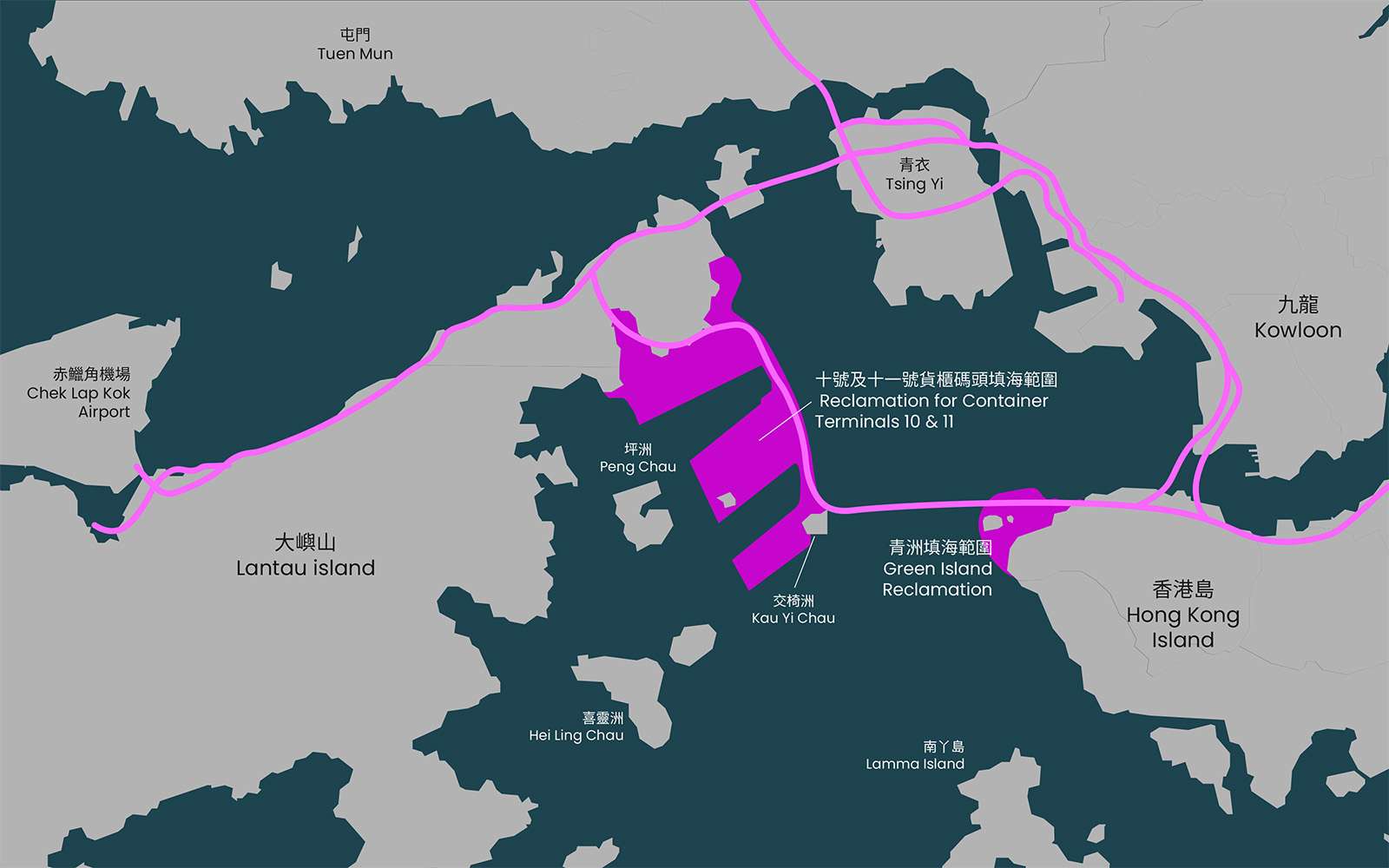

The original proposal was quite different. Instead of three separate islands, it was to be a single peninsula attached to eastern Lantau. Instead of housing 550,000 residents and a third Central Business District, it was to house two new container terminals.

It is difficult to convey the sheer size of this reclamation. It would have been four-fifths the size of Tsing Yi, an upside-down E extending from Penny’s Bay to Kau Yi Chau, wrapping around the island of Peng Chau to create two enormous new berths for future Cargo Terminals 10 and 11.

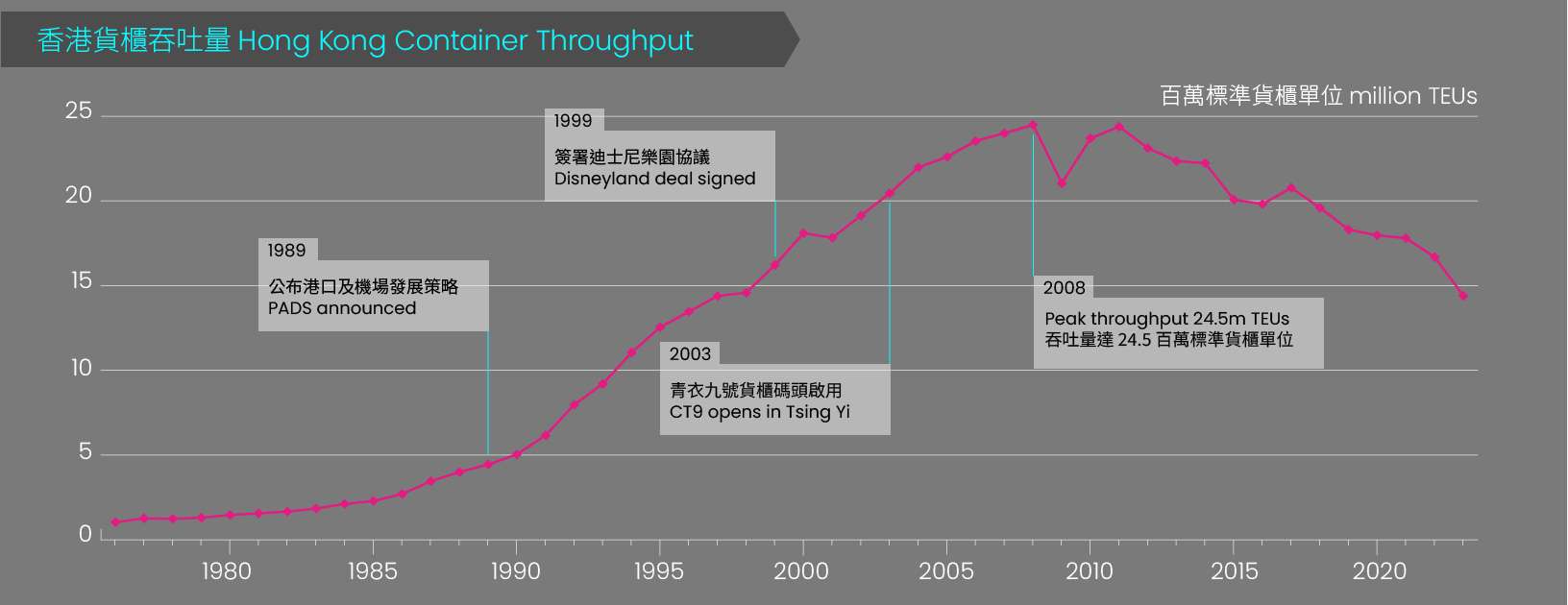

It was part of the government’s Port and Airport Development Strategy (PADS), a package of major transportation projects including the Chek Lap Kok Airport and the Tsing Ma Bridge announced in 1989. Dubbed the “Rose Garden Project”, it was seen as an attempt by the outgoing colonial government to pump up business confidence before the return to Chinese sovereignty.

In the original plans, the cargo port was to be connected to Hong Kong Island by a 4 km undersea tunnel from Kau Yi Chau to Kennedy Town. It would have been the longest tunnel ever built in Hong Kong at the time.

The Green Island Reclamation

At Kennedy Town, the tunnel would have landed on a vast new reclaimed area covering the space between Green Island and the Kennedy Town shoreline. It was intended to provide housing for 103,000 people and to anchor a highway link from Lantau to Central.

Green Island was just one of many reclamation projects put forward in a strategic planning document from the early 1990s called Metroplan, which was separate from but closely interlinked with PADS. It aimed to “thin out” Hong Kong’s urban core over a 20-year period by reclaiming enough land to spread out the population of the old districts. Huge reclamation projects were proposed from Tsing Yi to Kwun Tong on one side of the harbour, and from Green Island to Shau Kei Wan on the other.

But as we know now, a lot of these ambitious plans were never implemented.

First death

The Green Island reclamation was the first to be axed. The 1990s were not just a time of large-scale construction, they were also a time of growing environmentalism. In 1995, lawyer and Town Planning Board member Winston Chu founded the Society for the Protection of the Harbour and launched a signature campaign to stop Victoria Harbour from being turned into a “narrow river”. By 1996, his organization had succeeded in blocking the Green Island reclamation. In 1997, Legco passed the Protection of the Harbour Ordinance, a private member’s bill proposed by then-legislator Christine Loh. Over the next few years, advocacy and lawsuits by Chu and his allies put an end to all reclamation within Victoria Harbour except for the Phase 2 Central-Wanchai reclamation already underway, and forced the government to completely reevaluate its harbourfront planning policies.

However, the Kau Yi Chau cargo terminal project lay far outside of Victoria Harbour’s boundaries. What killed it off was much stranger: Disneyland. In 1996, Hong Kong’s cargo throughput grew more slowly than expected. In 1997, the Asian Financial Crisis struck. In 1999, the Tung Chee Hwa administration, searching for ways to attract tourist dollars, signed a deal with Disney. A gigantic cargo port would have spoiled the view from the Magic Kingdom at Penny’s Bay, so it was postponed indefinitely. In any case, the expected cargo volumes never appeared.

Cargo Terminals 9, 10 and 11 were planned in the late 1980s and 1990s based on exponential projections of Hong Kong’s cargo throughput. China’s opening up policy supercharged the mainland’s economy and Hong Kong’s container throughput grew by 14 times between 1977 and 1997. But by the time CT9 in Tsing Yi came online in 2003, Hong Kong’s growth was slowing, as new ports in the mainland started to compete for business. In 1998, the government had predicted that Hong Kong would be moving 33 million TEUs (twenty-foot equivalent units) of cargo by 2011. The actual figure was 24.4 million, and has declined steadily ever since, falling back down to 1998 levels by 2023.

Second life

Still, the cancelled projects never fully went away. The upside-down E of the Kau Yi Chau cargo terminal still appears on the Outline Zoning Plan for North-East Lantau, which still reserves more than 300 hectares for “the long-term expansion of the container port”. It has not been updated since 2005.

The idea of reclaiming the waters around Kau Yi Chau was resurrected in 2011, when the Civil Engineering Department was directed to explore reclamation options outside of Victoria Harbour to increase Hong Kong’s land supply. To assemble their initial long-list of 48 sites, they dug out old studies. They proceeded to narrow them down to 27, and finally to six options. Kau Yi Chau was one of the finalists, and was the option ultimately endorsed by Chief Executive Leung Chun-ying as the “East Lantau Metropolis” plan in 2014, then later rebranded as the “Lantau Tomorrow Vision” by his successor Carrie Lam in 2018.

Remote Kau Yi Chau seems to have been chosen partly because it offered a blank slate with no incompatible land uses or pre-existing residents to object. Another reason may have been because the transport network had already been planned long ago.

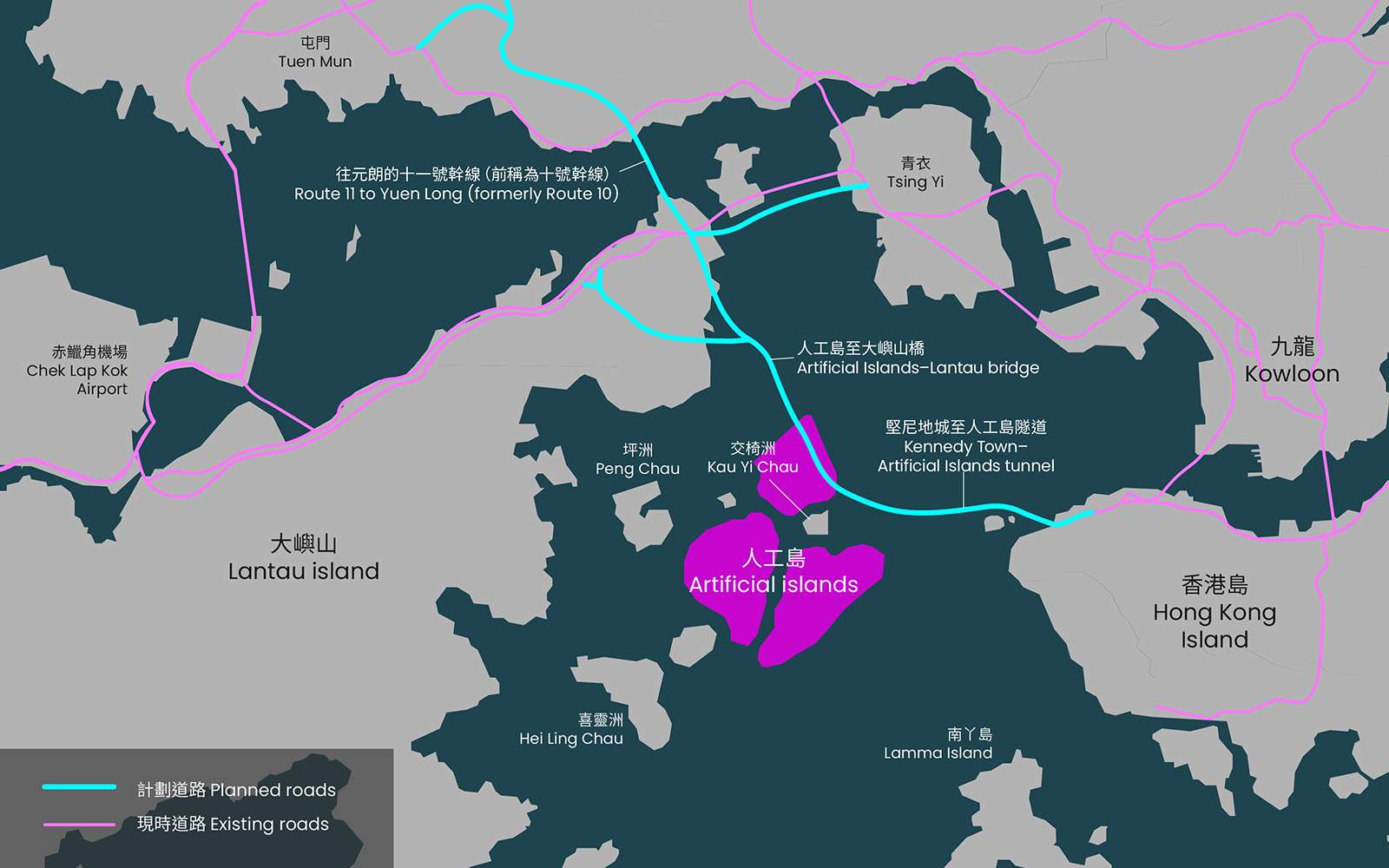

In the mid-1990s, the government had proposed to build Route 10 to serve the cargo terminal. First there would be a tunnel link from Kennedy Town to Kau Yi Chau, then the road would turn north, intersect with the North Lantau Highway, then bridge the water to Tsing Lung Tau (near Sham Tseng). Then it would tunnel north-westwards under Tai Lam Country Park, pausing at So Kwun Wat for an interchange link with Tuen Mun Road, before tunneling through to Lam Tei, swinging past Hung Shui Kiu and crossing the Shenzhen Bay to Shekou. It was designed to give lorries a direct route from factories in Shenzhen to the new cargo terminals, and a more direct route from Hong Kong Island to Chek Lap Kok Airport.

The government persisted in trying to build route 10 for several years after the cargo terminal was cancelled, even though there was no longer a need for it. The transport and feasibility studies had already been done. The project received hundreds of objections, with experts pointing out that those studies had overestimated traffic volumes by more than double. In the end, only the Shenzhen Bay Bridge section was built in a joint project with Shenzhen between 2003 and 2007.

20 years later, Route 10 is back, now renamed Route 11. The part between Lantau and Yuen Long is expected to be built by 2033. The link from Lantau to Hong Kong Island has been incorporated into the artificial islands project. However, with the Green Island reclamation cancelled and reclamation effectively banned in the harbour, the tunnel will have to make landfall on the Belcher Bay Promenade in Kennedy Town. In 2023, it was announced that the promenade would have to be closed for five years, and would be substantially narrowed to squeeze in the tunnel entrance and ventilation shaft.

Back on ice?

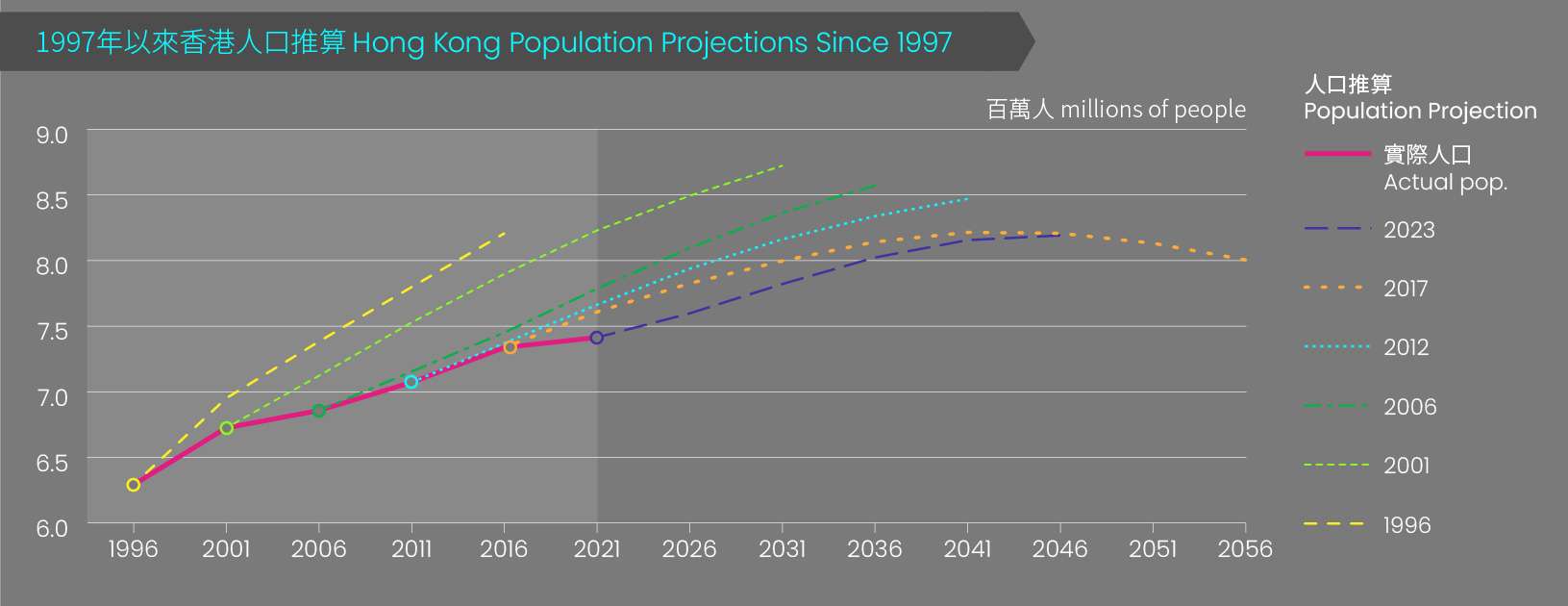

This article will not recap in detail the many controversies surrounding the Kau Yi Chau Artificial Islands project: its impact on marine life, its susceptibility to climate change, the limited public consultation, and its HK$580 billion price tag. However, we will point out a familiar pattern of using overly-optimistic predictions. In 2017, the Census and Statistics Department predicted that Hong Kong’s population would rise from 7.3 million in 2021 to 8.1 million by 2036. The islands were meant to house up to 550,000 people by the mid-2030s, absorbing two thirds of the projected increase.

In 2023, this projection was revised down to 8 million in light of Hong Kong’s emigration trend and low birth rates, but it is probably still too high. The government has actually over-estimated population growth during every single census cycle since 1997. Then in 2021, the government announced the Northern Metropolis Project, a belt of high-tech new towns across the northern New Territories that will house a million people. Combined with the Kau Yi Chau project, this would far exceed the housing need of the government’s own population projections up to 2046, when the population is supposed to peak at 8.2 million.

For several years, the government maintained it would pursue both projects simultaneously, until February 2024 when Financial Secretary Paul Chan announced that the artificial islands would be delayed for 2-3 years. The government’s post-Covid fiscal deficits put it in the position of having to prioritize. Perhaps it will only be delayed for three years, or perhaps for longer. However, if history is any guide, it will reappear again sooner or later.

For the 2024/25 Coastal Trail Challenge, we are collaborating with Parks and Trails to highlight stories behind some of the less well-known places along Hong Kong Island’s coast.

Sources:

Ove Arup & Partners et al., “Green Island Reclamation Feasibility Study – Final Report, Executive Summary”, Territorial Development Department, Hong Kong Government, September 1994.

PAPM Consultants et al., “Green Island Link Feasibility Study”, Highways Department, Hong Kong Government, February 1992.

Lawrence W. C. Lai, “The final colonial regional plan that lingers on: Hong Kong’s Metroplan”, Habitat International, v.41, January 2014, pp. 216-228.

Society for the Projection of the Harbour, “Our History”, last updated 2024.

Strategic Planning Unit, Land and Works Branch, “PADS: Port and Airport Development Strategy, Background Notes”, 1988, Hong Kong Government.

Economic Services Bureau Port and Maritime Division, “Port Development Strategy Review: Executive Summary”, 2001, HKSAR Government.

Pui-yin Ho, Making Hong Kong: A History of its Urban Development, 2018, Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing Inc.

Town Planning Board, “Approved North-East Lantau Outline zoning Plan No. S/I-NEL/12”, 8 November 2005, HKSAR Government.

Provisional Legislative Council Panel on Economic Services, “Lantau Port”, 10 September 1997.

Provisional Legislative Council Panel on Economic Services, “Northshore Lantau Development Study”, 3 November 1997.

Environmental Resources Management, “EIA Construction of an International Theme Park in Penny’s Bay of North Lantau and it’s Essential Associated Infrastructres, Section 2”, Environmental Protection Department, HKSAR Government, 2000.

Marine Department, “Port Container Throughput by Handling Locations and Seaborne/River”, 1990-2023, HKSAR Government.

Save Our Shorelines Society, “Major Review of Route 10”, submission to Legislative Council Panel on Transport, 27 April 2001.

Wilbur Smith Associates Limited, “Review of Proposed Route 10, Prepared for Route 3—Country Park Section”, Legislative Council Panel on Transport, 29 March 2001.

Samuel Yeung, “Is it the end of the road for the controversial Route 10 project?”, South China Morning Post, 16 December 2002.

Legislative Council Panel on Transport, “Background Brief on Route 10”, LC Paper No. CB(1)58/02-03, HKSAR Government, 15 October 2002.

Civil Engineering Development Department, “Kau Yi Chau Artificial Islands”, HKSAR Government, 2023.

Ove Arup & Partners, “Agreement No. 9/2011 Increasing Land Supply by Reclamation and Rock Cavern Development cum Public Engagement—Feasibility Study, Final SEA Report—Reclamation Sites”, Civil Engineering Development Department, HKSAR Government, 2014.

AECOM, “Technical Study on Transport Infrastructure at Kennedy Town for Connecting to East Lantau Metropolis”, Civil Engineering and Development Department, HKSAR Government, November 2017.

Census and Statistics Department, Population Projections, 1997-2016, 2002-2031, 2007-2036, 2012-2041, 2017-2066, and 2022-2046, HKSAR Government.