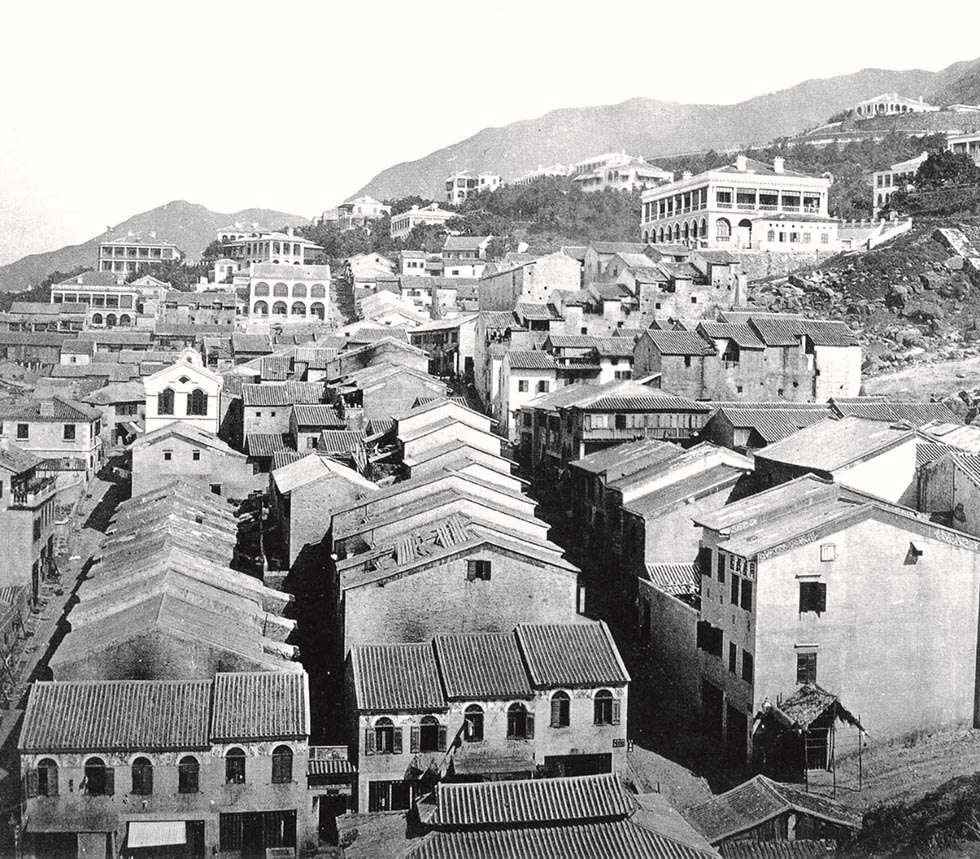

“First generation” tong lau in 1870s Tai Ping Shan. Source: Wikimedia Commons, public domain image.

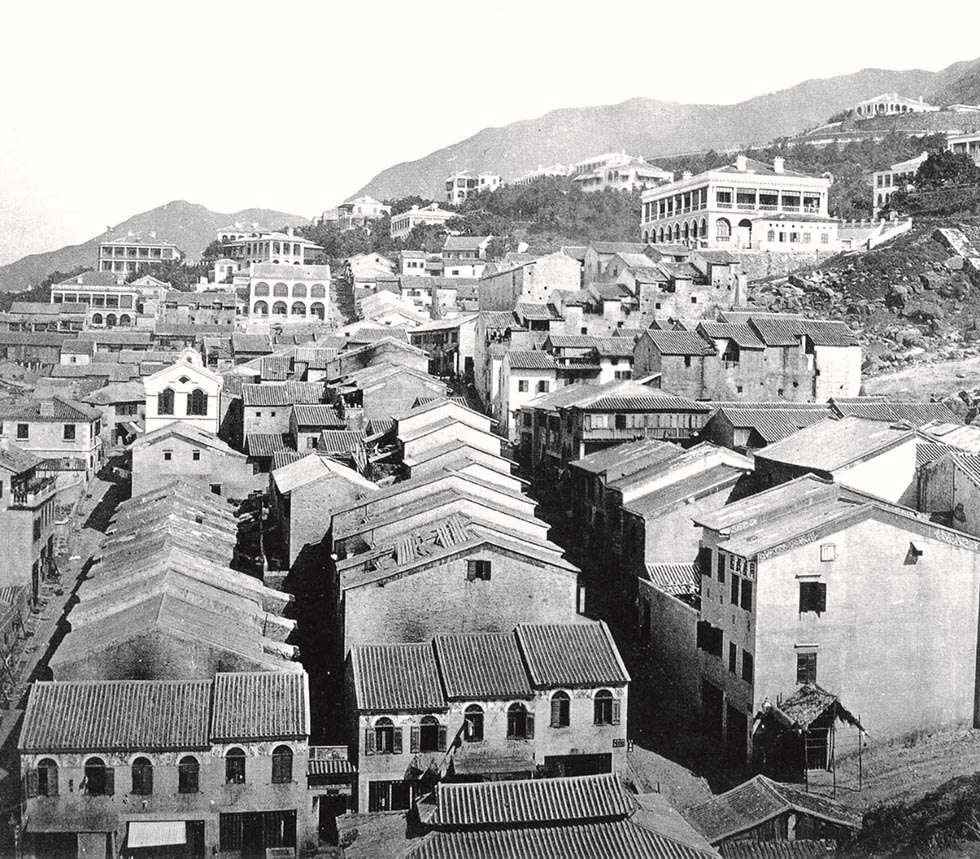

“First generation” tong lau in 1870s Tai Ping Shan. Source: Wikimedia Commons, public domain image.

A tale of fire, plague, shoddy construction, and unintended consequences

In present-day Hong Kong, pre-war shophouses (“tong laus”) are relatively rare; in 2021, the Urban Studies Institute documented about 170 clusters, comprising about 200 separate buildings. Moreover, while complete statistics on the ages of surviving tong laus are unavailable, the Antiquities Advisory Board’s (AAB’s) list of graded buildings, which includes about 100 tong laus, indicates that most are second and third generation tong laus.

The AAB’s list includes 46 tong laus from the 1930s, 40 from the 1920s, 6 from the 1910s and 6 from the 1900s. The sole known 19th Century example still standing is the Wing Woo Grocery Store at 120 Wellington Street, which is currently undergoing extensive renovation works by the Urban Renewal Authority as part of a large-scale redevelopment scheme. Why are there so few first generation tong lau left? Before proceeding, we should first define the terms.

According to architectural historians Lee Ho Yin and Lynne DiStefano, first generation tong lau were built in the 19th Century. They were long and narrow sparsely ornamented buildings with gabled tiled roofs built out of Cantonese blue-green bricks. Their width (about 4.5m) was determined by the length of fir beams that were used as structural support. Built wall-to-wall and back-to-back, their only windows were in the front. At the rear, there was a cook house with a hole in the roof for smoke to escape.

The second generation lasted from 1903 through the 1920s. These buildings were shaped by the 1903 Public Health and Buildings Ordinance which was passed in the wake of the 1894 bubonic plague outbreak. To improve ventilation and hygiene, houses were required to have toilets, back alleys, and backyards. Limits on building height and depth promoted the extension of verandahs over the public footpath. Building methods were in a transitional stage, combining steel reinforced concrete with traditional brick and wood.

The third generation started in the 1930s and lasted through World War II. Reinforced concrete was now used throughout structures. Many had Art Deco features, which was then the dominant worldwide architectural trend. Further changes to building regulations in 1935 generated the shared, naturally ventilated staircases that are this style’s defining feature.

What explains the sharp drop in tong laus surviving from before the 1920s? The passage of time alone does not seem to be an adequate explanation. Assuming the AAB did not somehow neglect to include a lot of older ones, there were several other factors: fire, plague, shoddy construction, and the unintended consequences of a 1920s rent control policy. Let us take them in order.

In the early decades of colonial rule, fires regularly wiped out tens or hundreds of buildings. Flames spread quickly among the tightly packed, partially wooden buildings. Often, the only way of stopping them was to demolish buildings with explosives to create fire breaks. Prior to the establishment of the Fire Services Department in 1868, fire fighting was handled not very effectively by the British military and various volunteer forces funded by local business associations.

Major fires were recorded in 1851, 1856, 1858, 1866, 1867 and 1868. Another catastrophic fire in 1878 destroyed around 400 houses between Gilman’s Bazaar in Sheung Wan and the Central Police Station (Tai Kwun). The Wing Woo Grocery was built after the fire in the middle of the destruction zone.

In 1894, an epidemic of bubonic plague killed 2,500 people. Smaller outbreaks recurred every summer until 1929. While the bacterium responsible was discovered in 1894 by two foreign scientists sent to Hong Kong to investigate, the means of transmission by fleas and rats was not yet well-understood. Many government officials still believed in “miasma theory”, which attributed disease to bad air rising from contaminated soil. This led them to identify Tai Ping Shan, a poor Chinese neighbourhood with inadequate water supply or drainage, and where three quarters of the houses were subdivided into tiny cubicles, as ground zero.

Colonial officials often blamed the poor living conditions in tong laus on Chinese culture. Some Chinese landlords exploited this perception, arguing that it was unfair to impose Western hygiene standards on them. But in fact, wealthy people of all nationalities, including Europeans, Indians, Parsees and Portuguese, built tong laus as rental properties. A third of the buildings in Tai Ping Shan had non-Chinese owners.

Despite heavy opposition from landlords, in October 1894, the Taipingshan Resumption Ordinance passed in Legco by one vote. The government demolished 417 tong laus with fire, removed the topsoil, and rebuilt the entire neighbourhood to better standards. Thousands of people were displaced. This gave rise to the Cantonese expression “洗太平地” (pronounced as “sai2 taai3 ping3 dei2”; literally, to clear Tai Ping land), meaning to wipe everything out.

Many early tong laus were built as cheaply as possible out of soft and porous green-blue brick. Builders saved materials by cutting corners, bribing Public Works Department inspectors to look the other way. After they were built, individual houses were sold without proper title deeds, which meant that nobody took responsibility for maintenance. As a result, building collapses were regularly reported in newspapers. In one especially serious incident in 1901, two houses that were less than 30 years old collapsed in Cochrane Street, killing 43 people. The subsequent investigation revealed that the owner had omitted structural beams and built hollow party walls to save money, then added an extra floor on top. Furthermore, the government reported to Legco that between May 1895 and August 1901, there had been 71 incidents of building collapse, including at least 30 whole houses and parts of other buildings.

In the early 1920s, Hong Kong’s housing affordability crisis reached intolerable levels due to inflation and worldwide grain shortages caused by World War I . In June 1921, Governor Edward Stubbs introduced a bill to freeze rents at December 1920 levels until the end of the year. Met with overwhelming public support, rent controls were renewed annually until 1925. However, to encourage the construction of more housing, new buildings were exempted. It had the opposite effect. Landlords evicted tenants, claiming that they wanted to redevelop. Sometimes, this only consisted of unnecessary repairs, but in many cases buildings were actually demolished. Owners saw redevelopment as a more reliable investment than new housing.

By 1923, Legco members were complaining that perfectly good buildings were being torn down, including one in Shanghai Street that was only two years old. Tenants had to offer landlords bribes (“shoe money“) to avoid being made homeless. If a tong lau had survived the preceding decades of fire, plague, and shoddy construction, it probably fell to the 1920s reconstruction craze.

In World War II, some 19,000 buildings were destroyed or damaged. Multiple waves of redevelopment followed. The few remaining tong laus are now the focus of conservation efforts and the subject of much nostalgia. Some have been converted into arts venues and restaurants. Yet beneath their carefully restored facades, they are reminders of a messy, unromantic history; one where from Hong Kong’s earliest days of urbanization, housing was seen as an investment vehicle, not a permanent place to live. Like the people who once lived in their dark and cramped cubicles, these buildings are survivors.

Cecilia L. Chu, Building Colonial Hong Kong Speculative Development and Segregation in the City, Routledge, 2022.

Lee Ho Yin, “Prewar tong lau: A Hong Kong shophouse typology”, Pre-war Tong Lau: A Hong Kong Shophouse Typology, A Resource Paper for the Antiquities and Monuments Office and Commissioner for Heritage’s Office, 19 April 2010.

Lee Ho Yin and Lynne D. Stefano, “Tong Lau: A Hong Kong Shophouse Typology”, Gwulo, 9 May 2016.

Patricia O’Sullivan, “The history of Hong Kong’s Fire Services Department, and the devastating infernos that forced the city to form a proper response force”, South China Morning Post, 5 June 2022.

Stephen N.S. Cheung, “Roofs or Stars: The Stated Intents and Actual Effects of a Rents Ordinance”, Economic Inquiry, Oxford vol. 13, i.1, 1 March 1975.

Urban Studies Institute, “Mapping of The Prewar Tenement and European Buildings on Hong Kong Island and Kowloon in 2021”, Facebook post, 2 March 2022.

Antiquities Advisory Board, “Search for Information on Individual Buildings (1,444 and New Items)”, database of graded buildings, last revised 19 December 2023, HKSAR Government.