The Surprisingly International Story of Hong Kong’s Earliest Lighthouses

And their Eurasian keepers

The year is 1869. Hong Kong has been under British rule for 28 years, and it has been nine years since the Second Opium War forced the Qing government to open eleven more treaty ports to foreign trade. The first commercial steamships arrived in Asia just a few years ago. The Suez Canal opened just this November, guaranteeing a flood of steamships for the 1870 tea season. Shipwrecks, already distressingly common, will be an even bigger problem. Hong Kong desperately needs some lighthouses.

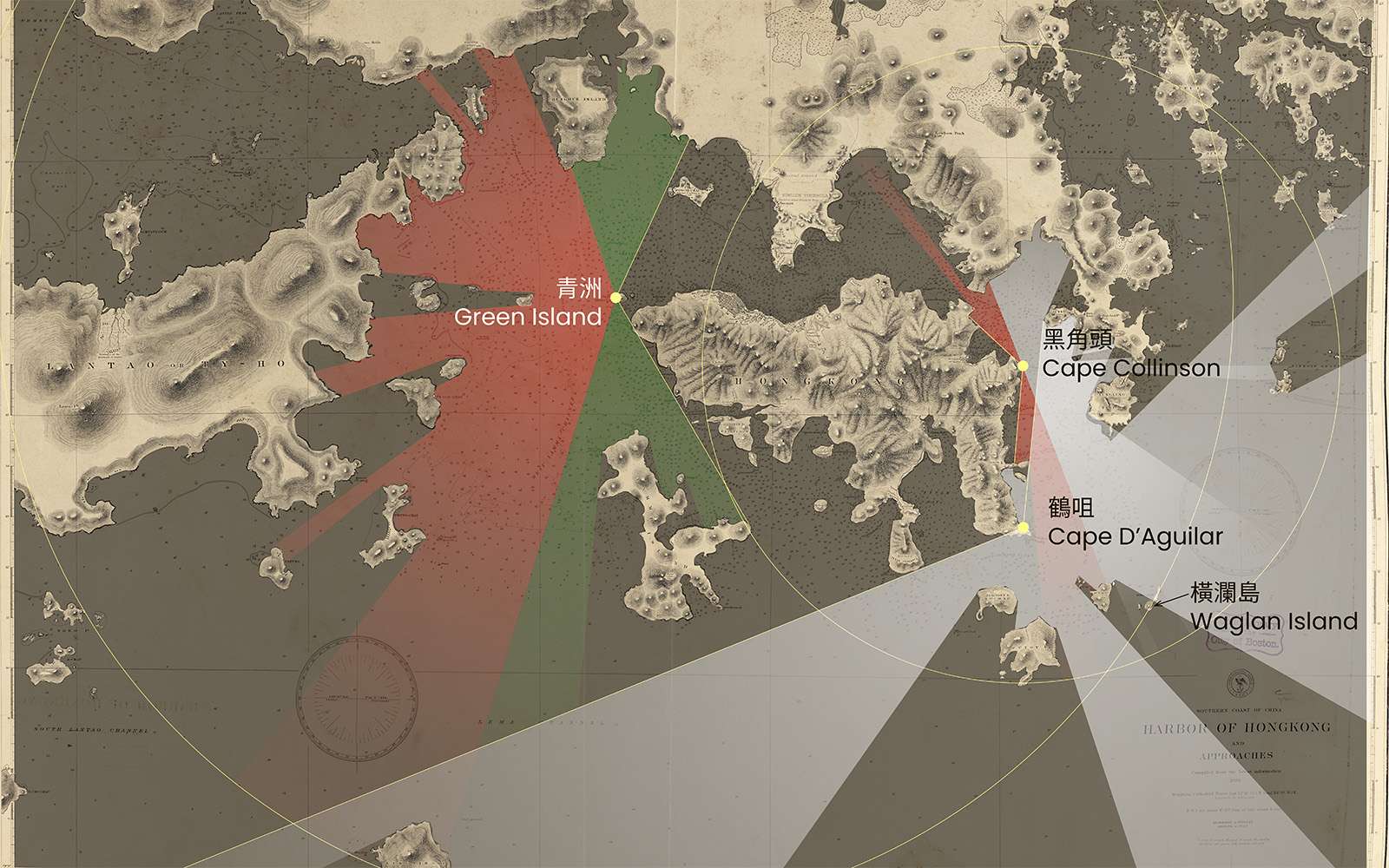

In 1875, Hong Kong’s first three lighthouses were built, one on Green Island, the second at Cape Collinson, and the third at Cape D’Aguilar (Hok Tsui). The Cape Collinson lighthouse had to wait until the following year to be lit because its apparatus was mistakenly shipped to the Cape of Good Hope. These three historic lighthouses are still in use today. Two (Cape D’Aguilar and Green Island), are declared monuments. If you are willing to make some detours while doing the Coastal Trail Challenge this season, you should be able to see them all.

Cape D’Aguilar Lighthouse

The Cape D’Aguilar Lighthouse is a 9.5m tall white granite tower perched on the southeastern tip of Hong Kong Island, an easy 1.5 hour hike from the Cape D’Aguilar bus stop. Declared a monument in 2005, this is the only one of the three that you can get close enough to touch. It was by far the brightest of the original three, with a first order Fresnel lens that could be seen 23 nautical miles (42.5 km) away on a clear night.

A Fresnel is made of prisms arranged in concentric circles to bend light into a focused beam so that it can be seen from far away. Perfected in the 1820s by French engineer and physicist Augustin-Jean Fresnel, they are a fraction of the thickness of conventional convex lenses, which made it possible to install them in lighthouses, replacing less effective parabolic reflectors. Fresnel lenses were manufactured in six sizes (“orders”) with first order lenses being the largest. To see one up close, visit the Hong Kong Maritime Museum in Central.

In the 1890s, the Cape D’Aguilar lighthouse was retired after another was constructed on Waglan Island, 5 km off the coast. The map above shows why Waglan Island was the better location—Cape D’Aguilar’s light was blocked to the south by several islands. The Waglan Island lighthouse was built by China’s government (more on that later), but Hong Kong acquired control over it a few years after Britain signed the 99-year lease on the New Territories. The Cape D’Aguilar lighthouse was only brought back into service after being fitted with an automated light in 1975.

Green Island Lighthouse

There are actually two Green Island lighthouses, the original 12m high one built in 1875, and a 17.6m high one built next to it in 1904-5. When the Cape D’Aguilar lighthouse was retired, the government wanted to transfer its lens to Green Island, but the original tower, which housed a fourth order lens, was too small. A replacement was built. Unfortunately, the public cannot visit Green Island without the Marine Department’s permission, but you can see the lighthouses from the Sai Wan Swimming Shed on the Mount Davis Coastal Trail. Bring binoculars for a better view.

The Green Island lighthouse originally used red and green light to warn ships of dangerous and shallow waters. White lights, which were brighter, were used to indicate safe waters.

Cape Collinson Lighthouse

Cape Collinson was the smallest, with a sixth order lens lighting up the immediate eastern entrance to Victoria Harbour. A white light was used to show the safest route and red lights to indicate dangerous rocks.

Of the three, it looks the least like a classic lighthouse due to the addition of a rectangular, utilitarian building in the 1960s. It can also only be seen through a fence. However, if you do want to see it, it is a 25 minute detour down Cape Collinson Path which branches off the start of Dragon’s Back Walk.

The globalized world of the 19th Century

Hong Kong’s early lighthouses were not just a sign of its growing importance as a port, they reflected a rapidly accelerating process of globalization that was neither smooth nor peaceful, but which brought together people, technologies and cultures. Coastal China of the late 19th Century was a more connected and global place than we think. Steamships accelerated the pace of international travel. In 1871, Hong Kong was connected to the international telegraph network via an undersea cable to Singapore. And while it took roughly 40 years for the first Fresnel lens to make it from Europe to East Asia, the next major lighthouse innovation took just three years to arrive.

Hong Kong’s first lighthouses had “fixed” (i.e. steady) lights, but soon adopted unique flashing patterns to identify themselves. This was done by revolving the lens apparatus around the lamp to produce sweeping beams of light. In 1890, France’s lighthouse service developed a way to float the lenses on liquid mercury, allowing them to spin 12-16 times faster. By 1893, such a light had been installed on Waglan Island by a leading French firm. This was possible because the Chinese government’s Imperial Maritime Customs Service, which commissioned it, was staffed almost entirely by foreign experts. This arrangement arose when foreigners took over the assessment of trade tariffs for the Qing government during the disruption of the Taiping Rebellion, but evolved into a permanent government department responsible for the management of ports. And while the relationship between the Qing government and its foreign staff eventually soured (a story too long to get into here), for decades they assisted the Qing’s Self-Strengthening Movement by upgrading China’s ports and providing revenues for military modernization.

Hong Kong’s population was also surprisingly diverse, including not just Chinese and British people, but various European nationalities, Indians, Parsees, Jews, and Portuguese (who were actually Macanese of mixed heritage). By the late 19th Century, there was also a distinct community of mixed-race Eurasians, who occupied an awkward social position. They were not fully accepted by either Chinese or European society, so they tended to marry each other. Some of Hong Kong’s richest families like the Ho Tungs, Chans/Tysons, and Kotewalls were Eurasian, but many others worked in administrative support jobs as clerks, bookkeepers and translators, acting as a buffer between the European upper management and low level Chinese employees. Until the 1950s, many lighthouse keepers were Eurasian.

The job tended to go to Eurasians partly because head lighthouse keepers had to be bilingual to communicate with their mostly Chinese assistants. On one hand, not many Europeans were fluent in Chinese, and on the other, until the 1950s, the colonial government did not trust Chinese people enough to be in charge of essential infrastructure. But perhaps another reason was that although the job of lighthouse was critical for safety and therefore well-paid, it was not very prestigious work.

Before automation in the 1970s, lighthouses were manned 24 hours a day. Early on, they burned acetylene gas and their clockwork had to be wound by hand every few hours. Later, they had electric light bulbs and diesel generators, but still needed supervision. During the daytime, there were duties like maintenance, signalling and monitoring the weather. While lighthouse keepers were not as isolated as we imagine—they worked with a team, and their families could visit them at less remote locations like Green Island—they still had to live offshore for weeks at a time.

The “Father of the Fishermen”

One of the few Eurasian lighthouse keepers that we know much about, thanks to oral histories shared by his family, was Charlie Beatty Allenby Haig Thirlwell (1918-1985), the “Father of the Fishermen”. When he was a child, interracial couples were still so stigmatized that certain government departments banned them from civil servants’ quarters, yet such relationships were not uncommon among European sailors, soldiers and policemen. Thirwell’s father was a British tugboat captain and his mother was Macanese.

Thirlwell served as a lighthouse keeper at Waglan Island and Green Island from 1937 until his retirement in 1973, and was known for befriending fishermen by trading fish and shrimp for vegetables from the lighthouse garden. He mentored their sons, taught them signalling and English, and helped found the Chai Wan Fishermen’s Recreation Club in the 1960s to promote dragon boat racing. It was in large part due to his efforts that it became a high profile sport.

Thirlwell spoke fluent Cantonese and Boat People dialect, sang Cantonese opera and sea shanties, and composed a dragon boat racing song that is still sung today. He was so dedicated to Boat People community issues that his family saw little of him on his days off. In the 1960s, when Boat People were threatened with displacement by the reclamation of Chai Wan, Thirlwell advocated to ensure the reconstruction of the typhoon shelter, and that the fishing families who gave up their profession would be rehoused.

Textbooks talk about subjects like colonialism and globalization in abstract terms: wars, treaties, trade flows, and empire, but rarely do they capture the nuance and richness of people’s lives. Charlie Thirlwell was born into one outsider group and dedicated much of his adult life to helping another. He had an almost absurdly patriotic British name (his three middle names being those of British military heroes), but elevated one of Hong Kong’s most famous traditions. His employers would have looked down on his parents, but trusted him with countless lives. So if you see a lighthouse on your hike, give a thought to their paradoxical, international history.

For the 2024/25 Coastal Trail Challenge, we are collaborating with Parks and Trails to highlight stories behind some of the less well-known places along Hong Kong Island’s coast.

Sources:

Louis Ha and Dan Waters, “Hong Kong’s Lighthouses and the Men who Manned Them”, Lectures delivered at the Hong Kong Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 3-4 May 2002.

Hong Kong Maritime Museum and City University of Hong Kong, “Online Exhibition of Seeing in the Dark: Hong Kong Harbour and Lighthouses”, May 2021.

Joe He and Yunting Guo, 《燈塔記憶-香港橫瀾島燈塔 謹以此片紀念燈塔管理員花維路先生》, (“Discover the Heritage of Waglan Island Lighthouse in Hong Kong”), City University of Hong Kong, 2021.

S.W. Poon, K. Y. Deng, and K.F. Man, “The Waglan Island: The Lights, the Elements and the Skies”, Lord Wilson Trust, June 2021.

S.W. Poon,《香港燈塔知多少》, Hong Kong Memory Subject Talk, 18 March 2002, Hong Kong Public Libraries.

Phil Edwards, “The Invention that Fixed the Lighthouse”, Vox,

Ticket to Know, “How Do Lighthouses Work?”, 18 April 2020.

Stuart Heaver, “Father of the fishermen’ Charles Thirlwell put Hong Kong dragon boat racing on the global map”, South China Morning Post, 25 February 2022.

Vicky Lee, “The Code of Silence across the Hong Kong Eurasian Communities” in Meeting Place: Encounters across Cultures in Hong Kong, 1841–1984, eds. Elizabeth Sinn and Christopher Munn, Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2017.

Richard S. Horowitz, “The Chinese Maritime Customs Service, 1843-1949: An Introduction”, Gale Contextual Essays: China and the Modern World.

Ting Ruan, “Lighting China’s Coast: The Chinese Maritime Customs and Lighthouse Construction”, Mariners: Race, Religion and Empire in British Ports 1801-1914, 2024, UK Arts and Humanities Research Council.