The Hidden Life of An Urban Oasis

12 hours at Bishop Hill

Between Shek Kip Mei and Prince Edward is a small hill known as Woh Chai Shan or Bishop Hill. It was relatively unknown until a government demolition crew unearthed a historic service reservoir in late 2020, but for years before the media attention and guided tours, this hill served the neighbourhood as an unofficial community centre.

In 2022-23, local non-profit organisation Parks and Trails conducted a study of backyard trails on hillsides near densely populated areas. Typically located outside of country parks on unoccupied government land, the management of backyard trails tends to be uncoordinated and sporadic, giving local residents the leeway to use and modify the space to their own needs. Parks and Trails installed infra-red people-counting sensors at key locations, including Bishop Hill, for several days in July-August 2022 and December 2022-February 2023. It found that the average backyard trail had between 400-500 visitors/day on weekdays and 700-800 visitors/day on weekends, with a few ranging as high as 1,800 visitors/day.

Bishop Hill was fairly typical, seeing around 500-600 visitors a day. However, unlike other backyard trails which occupy buffer zones between urban areas and country parks, Bishop Hill is entirely surrounded by development, with an estimated 324,000 people living within 15 minutes’ walking distance. Since there are no weekend hikers passing through, there is relatively little fluctuation in visitor numbers between weekdays and weekends, or winter and summer. It is an intensively used urban oasis, boasting a tight-knit community and a remarkable concentration of do-it-yourself structures from ping pong tables to shrines.

To supplement these statistics with real life observations, the City Unseen team visited Bishop Hill on two weekdays in March 2024, continuously walking its trails from 6:00-11:00 a.m. on the first day, and 11:00 a.m.-6:00 p.m. on the second. What follows is a somewhat unscientific composite picture of a typical day in the life of Bishop Hill.

6:00 a.m. to 9:00 a.m.

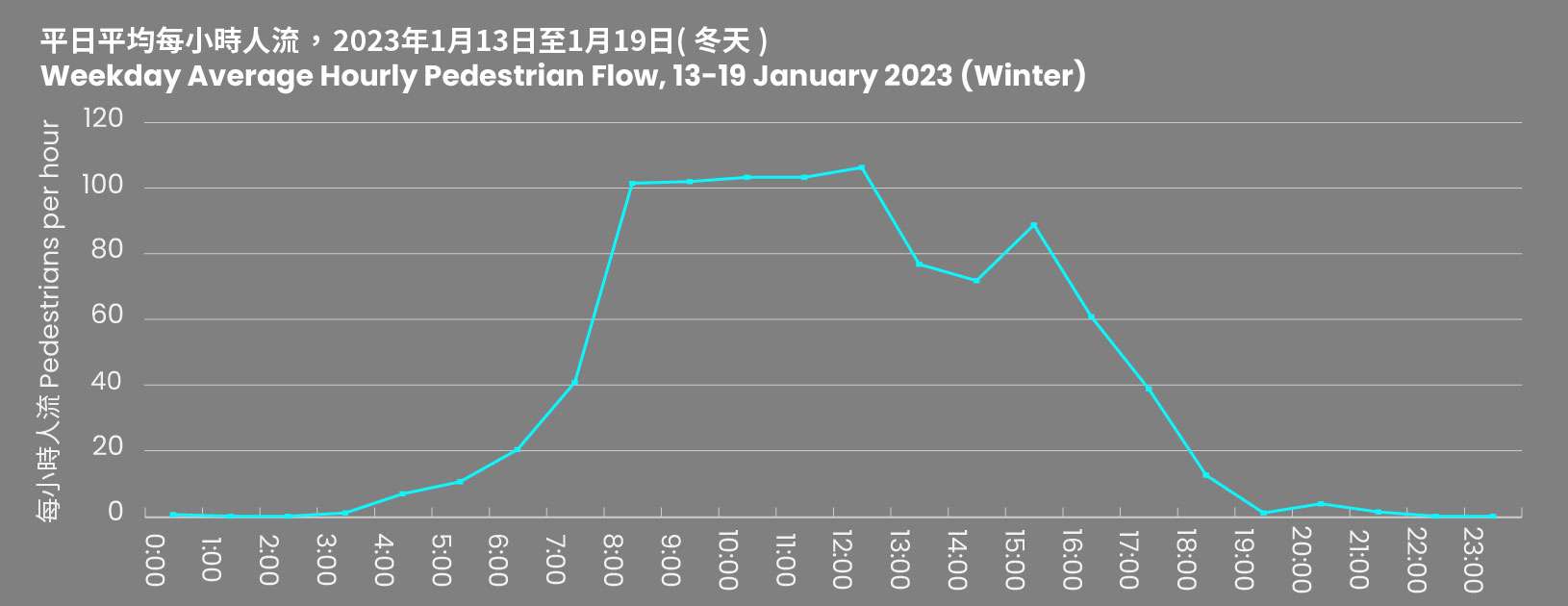

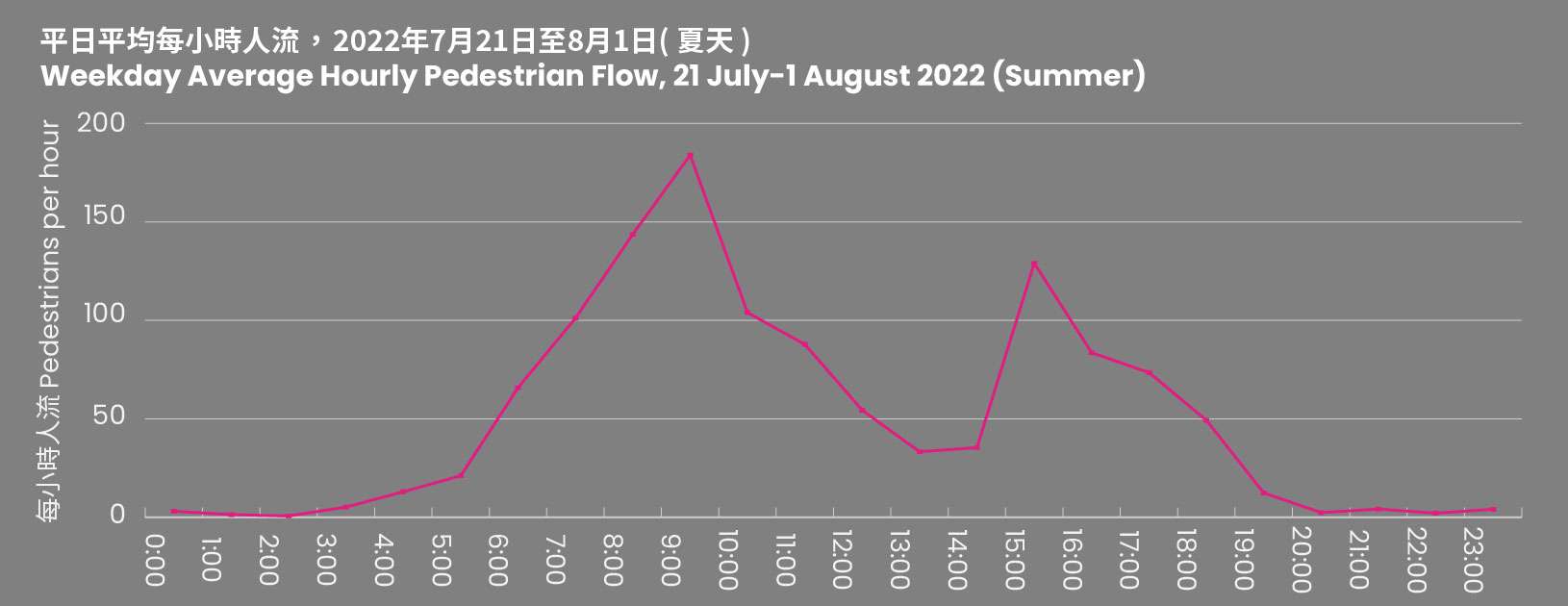

Shortly after 4:00 a.m., the sensors pick up the first signs of human activity. At there are no more than five or ten people an hour, but by 7:00 a.m. there is a steady stream. The earliest arrivals are already leaving, but more are arriving. By 8:00-9:00 a.m. there are over 100 people an hour.

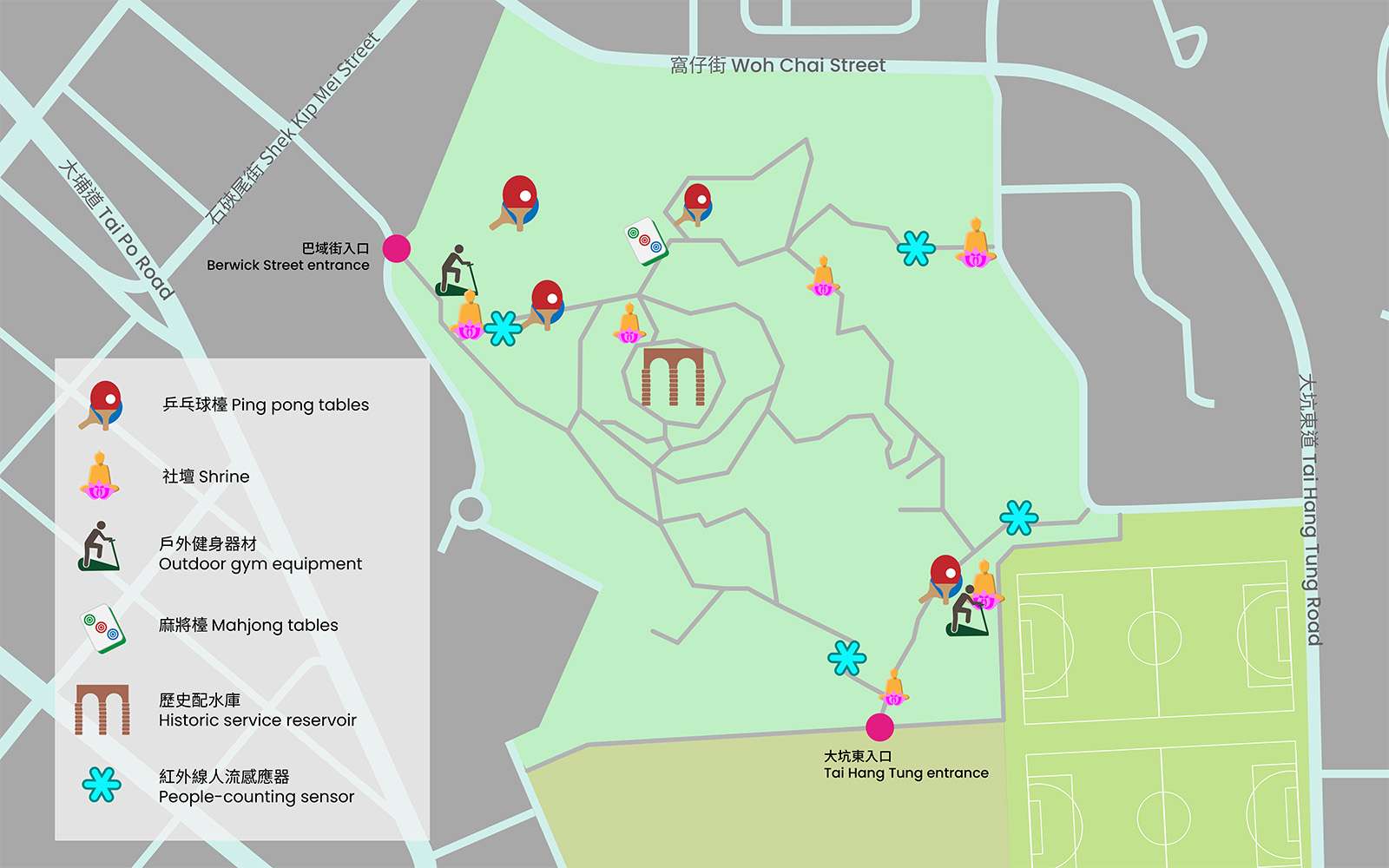

The busiest of the four sensors, which picks up 70% of all foot traffic, is located near the trail entrance on Berwick Street facing Shek Kip Mei Estate. The second busiest sensor, detecting about 20% of all activity, is on the opposite side of the hill at the trail entrance facing the Tai Hang Tung Recreation Ground.

At 6:00 a.m. on the day of our visit, the sky is still dark, but a few morning walkers are already out and about. Near the Tai Hang Tung trail entrance, there is an unofficial playground consisting of some ping pong tables and gym equipment built out of steel pipes and spare parts. The first visitor of the day, an elderly man, is seated at one of the exercise machines. Shortly, a woman arrives.

“Good morning, Mr Wong,” she calls, “you’re here all alone?”

“You’re early,” he replies.

“Only a bit. I didn’t come yesterday because it was raining.”

The regulars all seem to know each other. Repeatedly, we saw someone approach an activity space, and being greeted by everyone there.

So far, things are quiet, but incense has already been lit at the shrine opposite the playground, and six ping pong players have occupied the tables nearest the summit. One pair has strung an LED lamp on a wire above their table. As the sun rises, they unhook the lamp and put it away. There are at least 25 ping pong tables distributed across Bishop Hill. About half of them are clustered near the bottom where there is flat land, but more have been carried up and set up in groups of two or three, surrounded by green netting to stop balls from rolling downhill.

By 7:00 a.m., the DIY playground near the Berwick Street entrance is getting busy. There are 14 people in the small space, pedaling the exercise bikes, stretching their shoulders on the pulleys, meditating, and playing ping pong. People especially like the massage machines, rubbing their backs and limbs against the studded metal rollers. A woman who is stretching her leg over a metal beam says that she has been coming daily for the last 10 or 20 years. Even in the middle of summer, she says, the kaifong just show up earlier to avoid the heat. The sensor data confirms as much.

9:00 a.m. to 12:00 p.m.

9:00 a.m. is peak time. In the winter, a steady 100 people an hour are detected until the early afternoon. In the summer, the numbers hit 180 people an hour between 9:00 and 10:00 a.m., before rapidly decreasing. Mid-morning is also the busiest time for ping-pong players. By around 9:00 a.m., we count 16 players across various locations, the sound of rapid fire ping pong balls filling the air. These players will stay until around lunch time.

Like many backyard trails, Bishop Hill has several hillside shrines, which appear when unwanted religious statuettes are “rehomed” on hillsides because people cannot bear to throw them away. Tended by volunteer shrine keepers, they accumulate eclectic collections of deities: various incarnations of the Buddha and Guanyin, Guan Gong (the warrior god), Wong Tai Sin (god of health), Sau Sing Kung (god of longevity), Chi Kung (the drunken monk), and the occasional lucky cat or elephant.

Just after 9:00 a.m., Mr. So is watering the plants outside the Bishop Hill’s largest and most impressive shrine. It has two large golden Buddhas, an altar crammed with statuettes, a goldfish pond and a turtle pond. Mr. So, who built and maintains most of the hill’s exercise equipment, is the closest thing that Bishop Hill regulars have to a village chief. After surviving a SARS infection in 2003, and crediting visits to Bishop Hill for his return to health, he set out to build recreational spaces for his neighbourhood. Since then, a growing number of volunteers have coalesced around him. During the COVID-19 pandemic, he recruited out-of-work construction workers and raised $200,000 in donations to buy materials to build the shrine. He hopes that as the government transforms the historic reservoir into a tourist destination, they will leave his creations alone. He sees them as a way for retirees like himself to contribute to society. “You have to use everything you’ve got until the last moment,” he says, “otherwise you’re just waiting to die.” While he speaks, several people stop to light incense or nod to the statues on their way past. A volunteer grabs a broom and sweeps the ground around the altar.

At 10:00 a.m., 20 or 30 people troop up the stairs together from Berwick Street, the first of the Water Supplies Department’s three daily tours of the old service reservoir.

Near the summit is a large clearing where people have built a mahjong hut out of tarp and bamboo poles. During our first visit, the players had yet to arrive, but during our second visit, there were two games going by 10:30 a.m. A few stray dogs wander around. No-one seems bothered by them.

12:00 p.m. to 3:00 p.m.

The period after lunch sees a drop in activity. In the winter, the sensors detected a dip in foot traffic from 100 people an hour to around 70 between 1:00 p.m. to 3:00 p.m. In the summer, the hourly footfall fell to 35.

The early afternoon appears to be a time for maintenance. At one shrine, a woman is complaining to her companion about having to clean out the incense burner again. A little way up the hill, a man is watering a flower bed from a plastic jug. A very elderly man with a walking stick is scooping some cement powder into a plastic bag for some unknown purpose. At the Golden Buddha Shrine, one of Mr. So’s volunteers is cleaning the goldfish pond.

By 2:00 p.m., there are still several people exercising in the DIY playgrounds near the trail entrances, but most of the ping pong tables are empty; the players who remain are less expert than the morning crowd. Further uphill, there are a few people doing stretches or walking. Suddenly, there is a noise like two wooden boards slamming together. It turns out to be a kung fu practitioner, waving a five-foot-long chain whip around an isolated clearing. He would never be allowed to do this in a public park. Not everyone is happy to see him here, either. Two older women frown disapprovingly in his direction as they walk past.

A group of three young men arrive outside the gate to the historic reservoir at the top of the hill. Unfortunately, they soon realise that they cannot enter without a tour registration. They decide to come back tomorrow. A few minutes later, five better-prepared young people gain entry.

3:00 p.m. to 6:00 p.m.

In the late afternoon, there is a second, smaller rise in activity. Between 3:00 and 4:00 p.m., the sensors detected an average of 90 people in winter and 130 people in summer.

Another batch of ping-pong players arrives, this time filling up the large cluster of tables near the hill’s base. A little past 4:00 p.m., the mahjong players pack up and put away their table. School lets out, and at around 4:30 p.m. the playground near Berwick Street fills up with small children. They run in amongst the elderly users, playing on the swings and climbing the parallel bars. A child grabs one end of a shoulder-stretching pulley and is hoisted up into the air repeatedly by a grinning older man. “I’m bouncing up and down like a spring!” the child shrieks to his mother.

As the sun gets low, activity winds down. Between 4:00 and 5:00 p.m, the sensors detect 60 people; between 5:00 and 6:00 p.m., 40 people; and between 6:00 and 7:00 p.m., just 12. In summer, when the sun sets later, the sensors keep pinging with activity until 8:00 p.m. However, while a few people arrive as late as 5:00 or 6:00 p.m., by this time, most people are leaving.

After dark, Bishop Hill is quiet. The sensors continue to pick up one or two people late into the night, but the stray dogs largely have the hill to themselves. Then the sun rises, and the people come back.

References:

Thanks to Parks and Trails for allowing City Unseen access to the raw data from the Backyard Trails Pilot Project. To read Parks and Trails’ full reports on backyard trails, please see:

Carine Lai and Yeung Ha Chi, Backyard Trails Pilot Project Part 1: Exploring the Urban Fringe, Parks and Trails, April 2023.

Carine Lai and Yeung Ha Chi, Backyard Trails Pilot Project Part 2: Counting Trail Users, Parks and Trails, July 2023.