Veggies in Transit: How Vegetable Depots Bring Local Produce From Farm to Table

If you walk down main roads in the New Territories, you might notice buildings called “Vegetable Depots” near many village centres. These depots are mostly managed and operated by local farmers’ cooperatives, and to this day, still play a role in the agricultural supply chain.

Currently, there are approximately 30 vegetable depots across the New Territories. Of these, 26 are part of the Federation of Vegetable Marketing Co-operative Societies, while the rest operate independently. Most date from the 1950s and 1960s, but with the decline of local agriculture, and the fact that crops are no longer required to be sold through the quasi-governmental non-profit Vegetable Marketing Organization (VMO), their operations have diminished in recent years. Many vegetable depots have ceased operations, while others no longer operate on a daily basis.

A farmer’s first stop

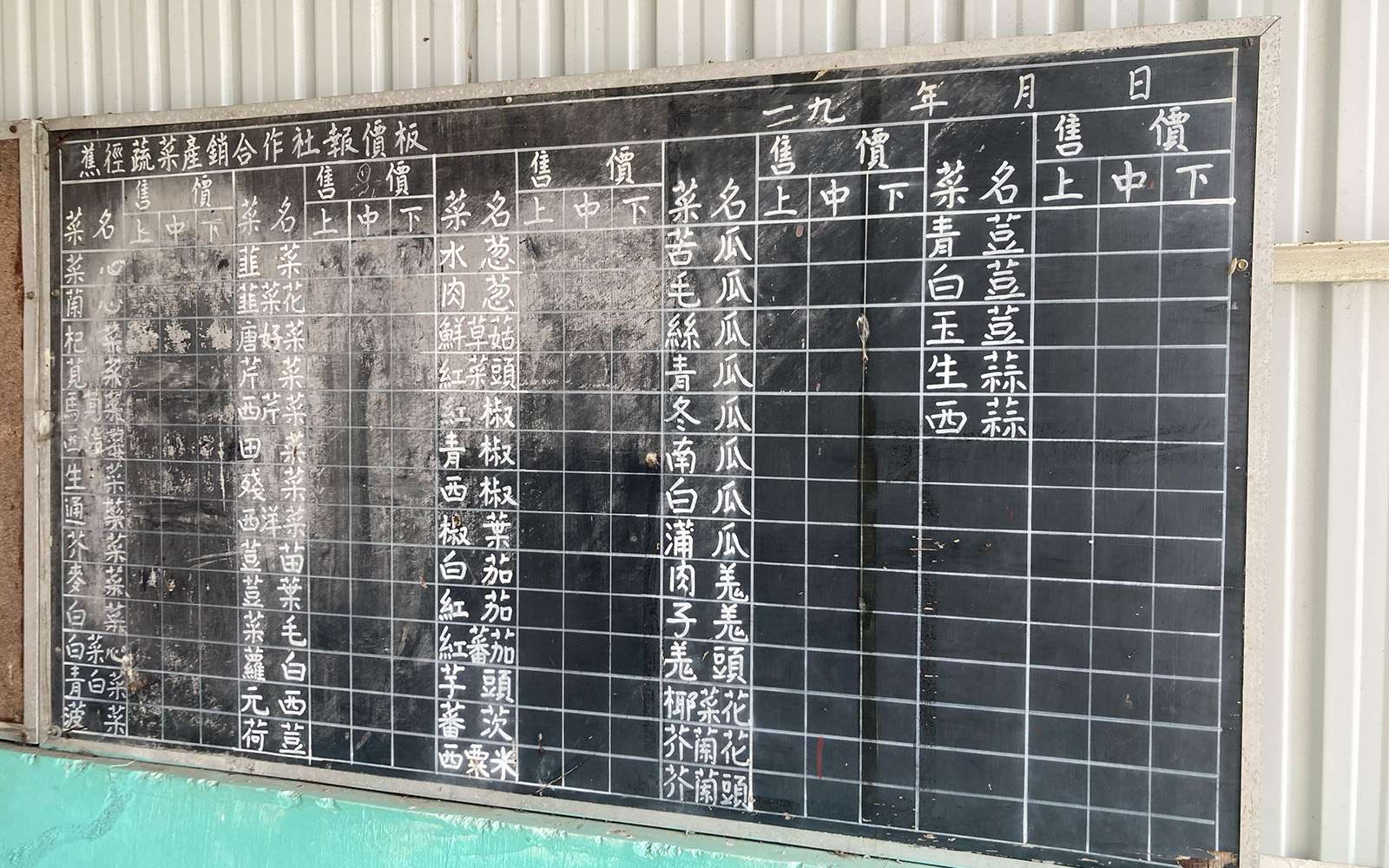

Although vegetable depots vary from village to village, they generally share several major elements: a “basket room” for offloading vegetables, an office, and a loading platform. In the past, farmers would take their harvests to the depot, placing them into standardized designated baskets before weighing them on a scale outside the basket room. Buyers at the depot would record the type, quality and weight of the vegetables on a “basket ticket”, which would be attached to each VMO basket. Upon arriving at the VMO (at the Cheung Sha Wan Wholesale Vegetable Market), the cooperative’s sales representative negotiates prices with buyers. Once both parties reach an agreement, the sales representative fills in the price and other details on the ticket, which the buyer then submits and pays in cash at the VMO cashier’s office.

Vegetable depots typically have loading platforms because previously, each cooperative operated its own delivery truck. After delivering produce to the VMO, the trucks returned to the depot to wait for the next day’s harvest. However, due to a significant drop in agricultural production, many vegetable stations no longer have their own trucks and have shifted to hiring vehicles on an as-needed basis. Nowadays, you no longer see trucks parked outside most depots.

Cooperatives with a more geographically spread out member network may have a main depot plus one or more “satellite depots,” to which members deliver their vegetables by handcart. The cooperative’s truck would then swing by each one to collect the produce. Satellite depots can vary significantly in size. For example, the Tai Kong Po satellite depot, under the Shek Kong main depot, is a solidly built, spacious structure, while the Sun Yau Vegetable Depot’s satellite in Yau Tam Mei village is just a tiny shed that is only opened during delivery hours.

The history of vegetable depots

Most of Hong Kong is hilly terrain, so the British did not cultivate cash crops as assiduously as in other colonies like Malaya or India. This allowed traditional agriculture to be preserved in the New Territories. Rice cultivation was the primary focus, supplemented by small-scale poultry and livestock farming, while non-staple foods such as vegetables were mostly imported from Guangdong and other places. By the 1930s, after the Seamen’s Strike and the Great Depression, the colonial government in Hong Kong had begun to put more emphasis on local farming, establishing government departments to guide agricultural production.

Following the outbreak of the Pacific War in 1941, Hong Kong endured three years and eight months of Japanese occupation, during which agricultural development stalled. After the end of World War II, civil war broke out in mainland China, causing many refugees to flee to Hong Kong.

At the same time, many male indigenous New Territories villagers left Hong Kong to seek better opportunities overseas. Landowners began renting their fields to newly arrived refugees, many of whom were skilled in vegetable cultivation. Over time, vegetables became the dominant crop in the New Territories.

In 1946, the government established the Vegetable Marketing Organization to stabilize the prices of agricultural produce. Through the VMO, the government intervened in the transport and sale of agricultural produce, hoping to replace private middlemen with a fair market system by requiring that all crops in Kowloon and the New Territories be delivered to the VMO for wholesale distribution. However, some vegetables still made it to market through other channels, such as dawn markets, direct sales, and private buyers.

The government welcomed the involvement of refugees in agricultural production and even issued “Crown Leases” through the District Office, granting them the right to cultivate crops on government land. In addition, the government provided agricultural technology training and irrigation infrastructure to support agricultural development.

Initially, the government set up collection points for vegetables across the New Territories. With immigrants bringing new farming techniques to Hong Kong, there was a rise in agricultural productivity. However, this soon led to disputes among various agricultural communities due to market competition and resource allocation. To resolve this issue, the government set up the Cooperative and Marketing Department to encourage the farming community to form cooperatives within their local areas. The committee, elected by the member farmers, was responsible for coordinating the logistics and sales at VMO. In 1951, the Fanling Vegetables Marketing Co-operative Society was established, followed by the formation of cooperatives in different areas of the New Territories.

How do agricultural cooperatives work?

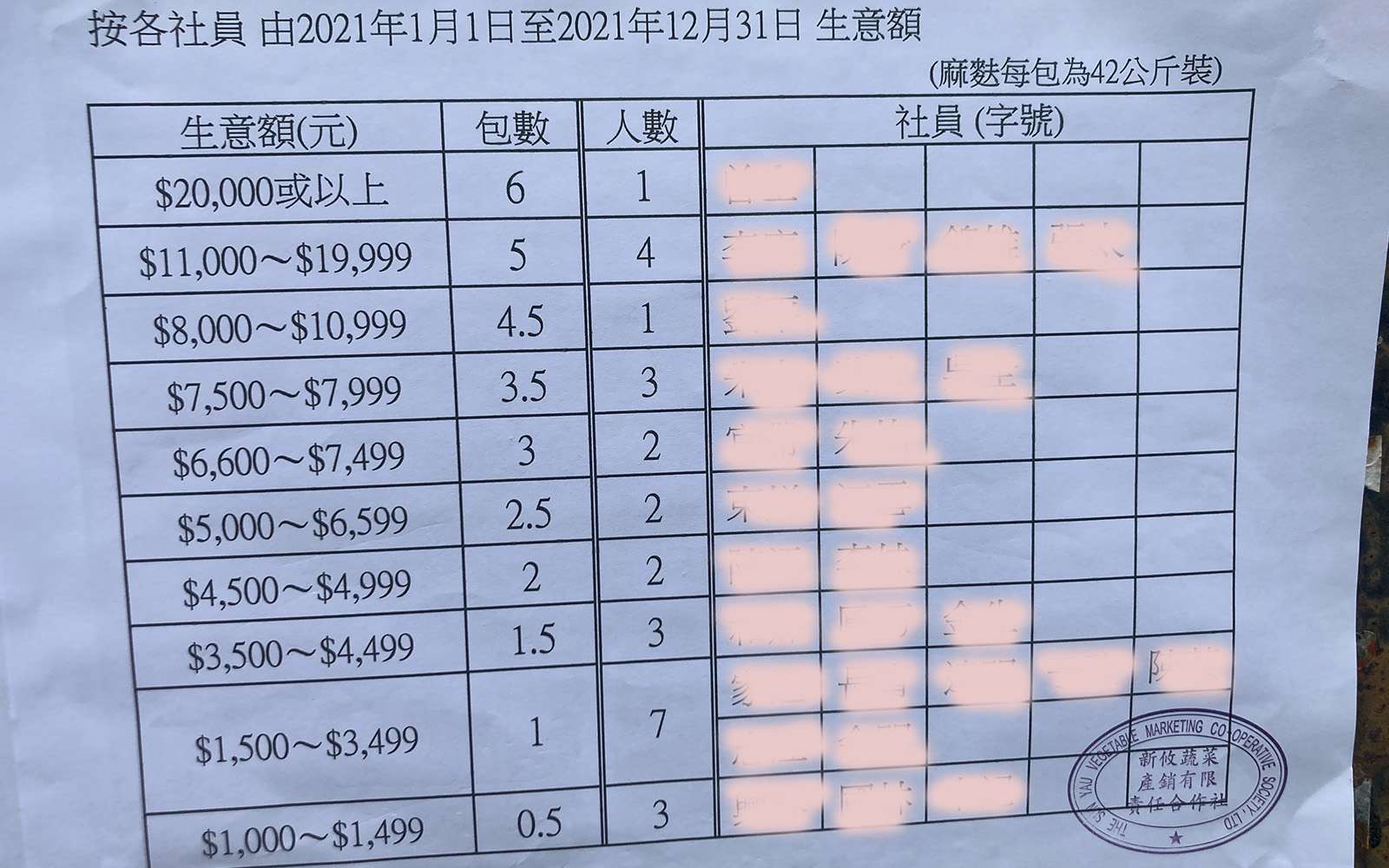

Farmers harvest crops from their fields in the middle of the night and deliver them to the vegetable depot. The cooperative then consolidates their produce and transports it to the Cheung Sha Wan Wholesale Vegetable Market. The sales revenue is handed over to the farmers after deducting commissions for the Vegetable Marketing Organization (VMO) and the cooperative. The government also sends out information and promotes agricultural policy to farmers through cooperatives. Cooperatives also help their members purchase and distribute fertilisers, pesticides, and staple goods.

Additionally, since farmers may not have sufficient funds to buy farming supplies before the growing season, cooperatives also provide small loans. In 1954, the government established the J.E. Joseph Trust Fund to grant farmers’ cooperative societies loans for development or working capital, and cooperative societies would lend this money to members at low interest rates. That is why some cooperative societies are named “Marketing and Credit Co-operative Society Limited” or “Credit Co-operative Society Limited”.

Vegetable depots in the New Territories have witnessed the rise and fall of local agriculture over the years. Today, the quantity of vegetables traded through cooperative societies and the VMO is much lower than before. Prices offered by the VMO are not particularly high, making new farmers unwilling to sell through them.

However, for several reasons, many older semi-retired farmers still prefer to sell their vegetables through cooperative societies. First, the locations are convenient, saving them the trouble of travelling long distances into the city. Second, they do not have to find customers themselves. Third, vegetable depots continue to provide fertilisers to their members according to the quantity of vegetables each member delivers each season.

Nevertheless, with ongoing development projects in the New Territories, some vegetable depots, such as those in Kwu Tung and Lung Chau, will soon disappear due to land acquisition.

(This article is written by contract researcher Ng Cheuk Hang.)

References:

Chow Sze Chung, <夕陽的光:誰說香港沒有菜園> (“The light of sunset: Who said there is no vegetable farm in Hong Kong”), Art and Culture Outreach, 2022.

Iu Kow-choy, <十九及二十世紀的香港漁農業傳承與轉變-下冊:農業> (“The Heritage and Transformation of Fishing and Agriculture in Hong Kong in the 19th and 20th Centuries, Volume 2: Agriculture”), Cosmo Books, 2017

Chen Yuli, <香港農業合作運動研究:以蔬菜產銷合作社為例(1945-1997)> (“Study of the agrarian cooperative movement in Hong Kong: vegetable marketing cooperative societies as an example (1945-1997)”), The Chinese University of Hong Kong, 2007