Ghost Buildings

The traces of long-demolished buildings can still be found across the city

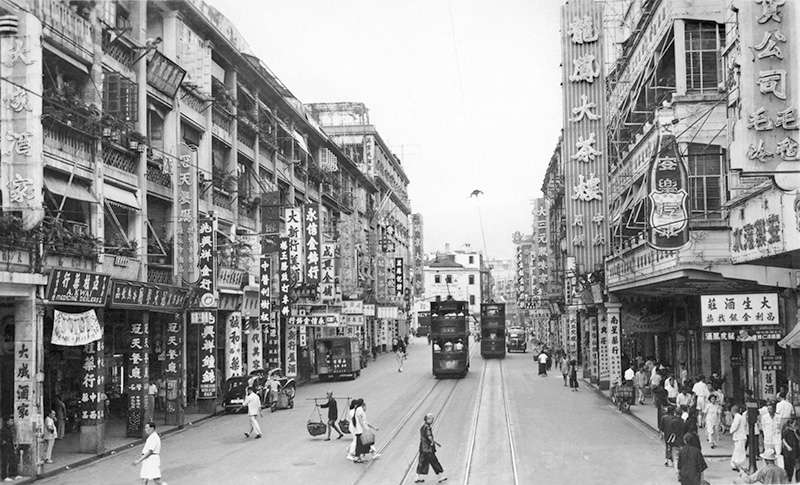

Throughout its history, Hong Kong has seen multiple waves of redevelopment. Out of the roughly 41,000 buildings in the Home Affairs Department’s Database of Private Buildings, only about 180 of them are listed as having been built before 1946. Yet buildings can leave traces long after they are demolished. Cities are iterative, layering thousands of individual decisions shaped by money, regulations, technologies, social norms and convenience. Sometimes, the earlier layers can be seen like ghostly imprints.

Orphaned pillars

Walking down the street, you may encounter a lone pillar with no apparent purpose. Their decorative moulding is a clue that they are older than the plain 1950s or 60s tenement buildings on either side. They are the remnants of pre-war tong laus.

Tong laus are wall-to-wall shophouses thought to have originated in Southern China in the late 19th Century, and are also found in Penang, Singapore and Macau. They are a hybrid architectural style that developed in conjunction with local building codes and practices. In Hong Kong, their deep pillar-supported verandahs developed as a way to obtain more floor space by extending over the public footpath, especially after the Public Health and Buildings Ordinance of 1903 restricted building heights to 4 storeys and required developers to leave space for light wells and alleys in the back.

While tong laus were subdivided into bedspace cubicles since the earliest colonial days, the huge influx of refugees after World War II made overcrowding even worse. In 1955, the government passed a new Buildings Ordinance allowing for higher densities, setting off a wave of redevelopment. Walk-ups could now reach 9 storeys, and buildings with elevators could be taller depending on the width of the street. Yet some old pillars survived—not for structural reasons, since cantilevered post-war buildings no longer needed them—but because of property boundaries.

In the pre-war period, wealthy people would build entire rows of tong laus to rent out. Over time, individual houses divided among different owners. This would later cause problems for redevelopment. Each sub-lot’s boundaries passed through the middle of the party walls dividing each house from its neighbour. Essentially, each party only owned half the thickness of the wall. Since knocking down or altering a party wall would affect the structural safety of the neighbouring building, the Buildings Ordinance required developers to obtain the permission of both parties.

In many cases, developers did not wait to get permission from the other owner or owners. When one building was redeveloped, the party wall—including the pillar—had to be left in place or the building next door would collapse. When the other building was also redeveloped, the party wall was often left untouched. From the 1950s onwards, it became increasingly common to sell individual flats instead of entire buildings, and so new buildings had multiple owners, which made it even harder to get permission. Therefore, although the developer lost some floor space due to having to erect another wall entirely within their own lot boundary, this was still more profitable than waiting.

71 Des Voeux Road. July 2009: Two pre-war four storey tong laus stand next to a six storey tong lau (left) from in 1964.

January 2017: The building on the right was demolished, leaving 2 pillars.

December 2020: The second pre-war tong lau was demolished, leaving only one pillar behind.

Shadow buildings

Sometimes, there are exposed party walls where a building was demolished but the gap was not filled. There, you can often find the outline of its vanished next door neighbour.

In the photo at the top of this article, a remnant party wall clearly shows the outline of a gabled roof. This indicates that it was probably built before the 1935, when most tong laus had stone or brick partition walls, wooden roof beams, and sloped roofs. After the widespread adoption of reinforced concrete, roofs tended to be flat.

Another example below shows the outline of a four storey building which was probably similar to the still-standing green building. Decorative moulding is visible on the front of the surviving party wall.

The X shaped bracing was not original to the demolished building, but added afterwards to ensure the brown building’s stability. Since the pink building on the left was built according to post-1964 building regulations, which generate tall narrow towers instead of bulky tenement blocks, the brown building could no longer rely on its neighbour for structural support. Therefore, the government required its developer to add the bracing.

Tetris buildings

Occasionally, you might look up and notice a strange gap between two buildings, with one extending over the space like a Tetris L-block that landed the wrong way. These are another artefact of property boundaries. It used to be common for two tong laus to share one staircase, with the lot boundary dividing the staircase in half.

When one owner redeveloped their half, they could not demolish the staircase because it was still needed by the other half. The taller replacement building therefore wrapped over the top of the stairwell up to the lot boundary to maximize floor space. This was inefficient; not only did the developer lose the floor area occupied by the stairs, they would have to build a second separate staircase to serve the new building. Yet the financial benefits outweighed the costs. When the second half was finally redeveloped, the stairs were demolished, but the space could not be filled in because the they only owned the half up to their lot boundary. An empty space was left behind. Next time you see a Tetris building, you are most likely looking at the ghost of a staircase.

Sources:

Special thanks to Mr. John Lam, founder of Glamorous Building and Engineering Consultancy.

Christopher DeWolf, “The Mystery of Hong Kong’s Ghost Pillars”, Zolima Citymag, 25 July 2018.

John Lam, “Common Staircase Shared by Adjoining Lot in Hong Kong”, Glamorous Building and Engineering Consultancy, 2 December 2020.

Lee Ho Yin, “Pre-war Tong Lau: A Hong Kong Shophouse Typology”, resource paper to the Antiquities and Monuments Office and Commissioner for Heritage’s Office, 19 April 2010.

Lee Ho Yin, “Hong Kong Composite Buildings: Modern Architectural Heritage of the 1950s and 1960s”, The Conservancy Association Centre for Heritage, lecture given 8 February 2013.

Hong Kong Institute of Surveyors, “Short Guide: Maintaining Your Historic Buildings”, September 2022.

Buildings Department, “Code of Practice for Demolition of Buildings”, 2004, Buildings Department, HKSAR Government.