Hong Kong’s Lost Streams – Part 1: The Disappearance of Urban Streams

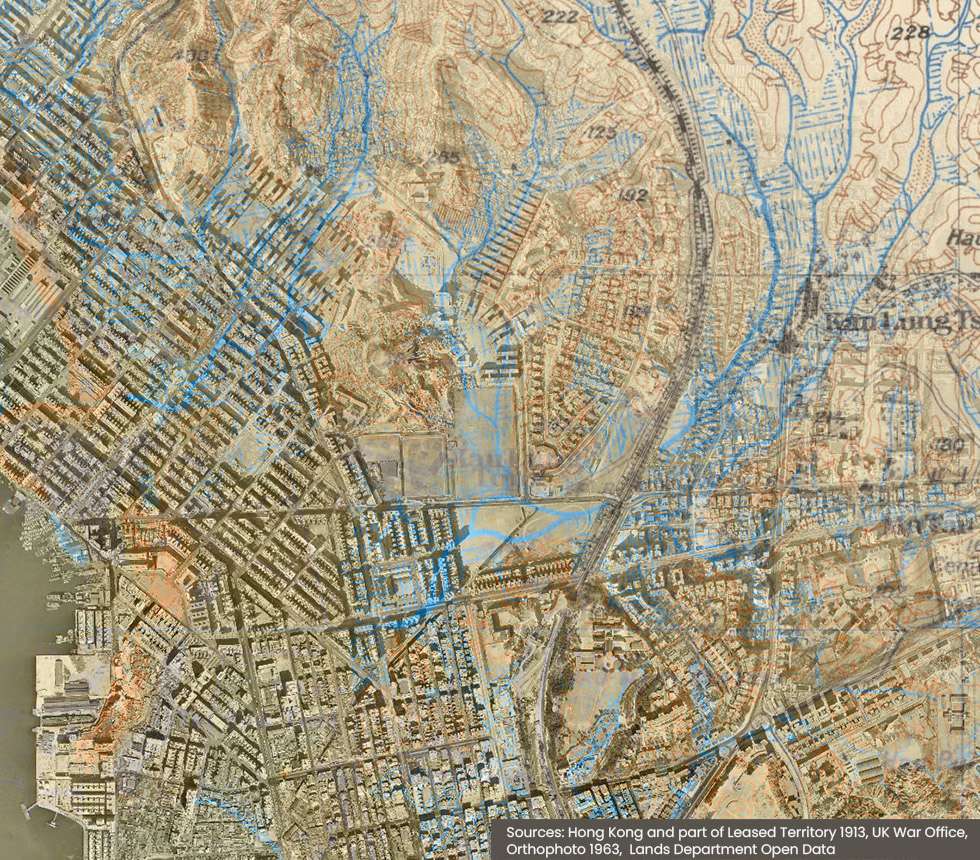

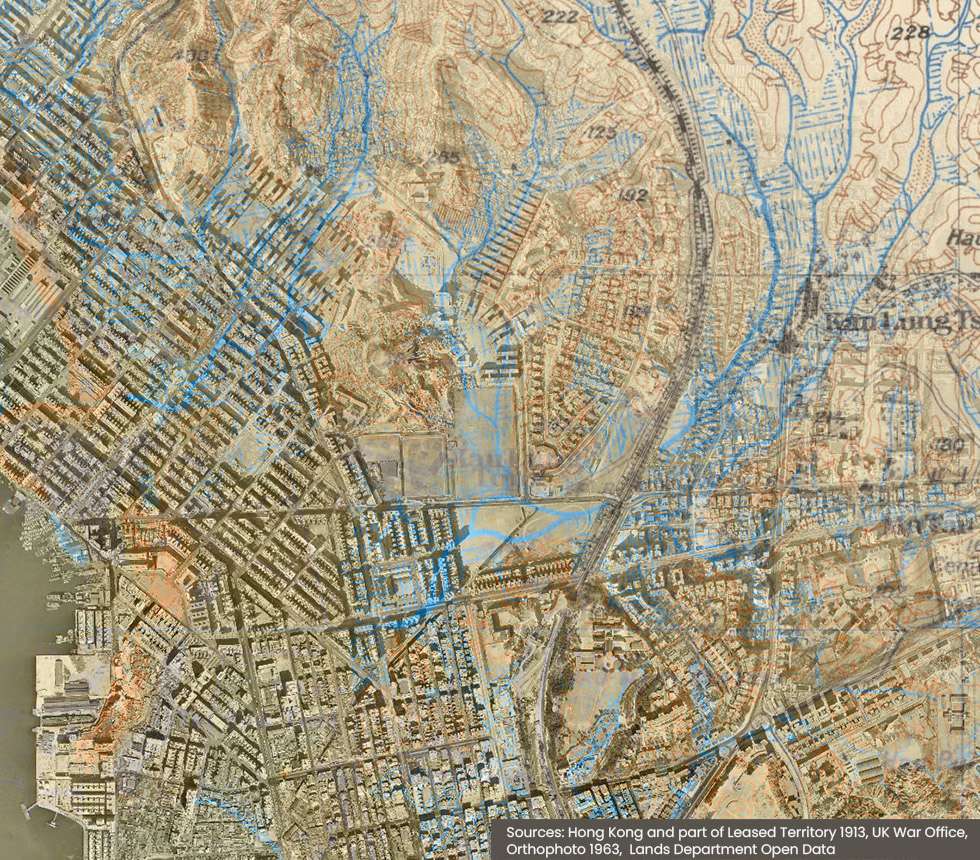

If you look at an old map of Hong Kong, one of the first things you will notice are the streams undulating their way down the hillsides, blanketing the land in a web of blue filaments. They still exist—Hong Kong has over 200 rivers and streams, most of them small—but as a city dweller you would hardly notice them.

Frequent hikers and morning walkers will have encountered plenty of mountain brooks. New Town residents live beside concretized riverbeds like the Shing Mun River. But in urban Kowloon and Hong Kong Island, apart from a few small artificial channels, streams are no longer visible at all. They have been buried beneath the pavement.

Clues to Subterranean Streams

These subterranean streams have nevertheless left traces of their existence. Place names with “涌” (chung) meaning stream, like Kwai Chung; “坑” (hang) meaning depression or ditch, like Tai Hang; or “塘” (tong) meaning pond, like Kowloon Tong, point to former hydrological features. In Tai Hang, there is a Wun Sha Street (“Cloth Washing Street”), where commercial laundries used to wash clothes in an open nullah.

The Anglo-Indian word “nullah”, found in street names like “Nullah Road” and “Stone Nullah Lane”, is a legacy of colonial-era engineering. Derived from the word “nala” in Hindi, it originally referred to natural gullies with fast-flowing intermittent streams, but evolved to mean man-made drainage channels.

Underground waterways have also left physical imprints. The long, narrow sitting-out area that extends down the centre of Nam Cheong Street in Sham Shui Po was an open nullah until the 1960s. After being covered, the space was occupied by a temporary market until the 1980s. The palms and Australian bottlebrush trees planted there were chosen for their small root balls because the concrete drain underneath leaves little space for soil.

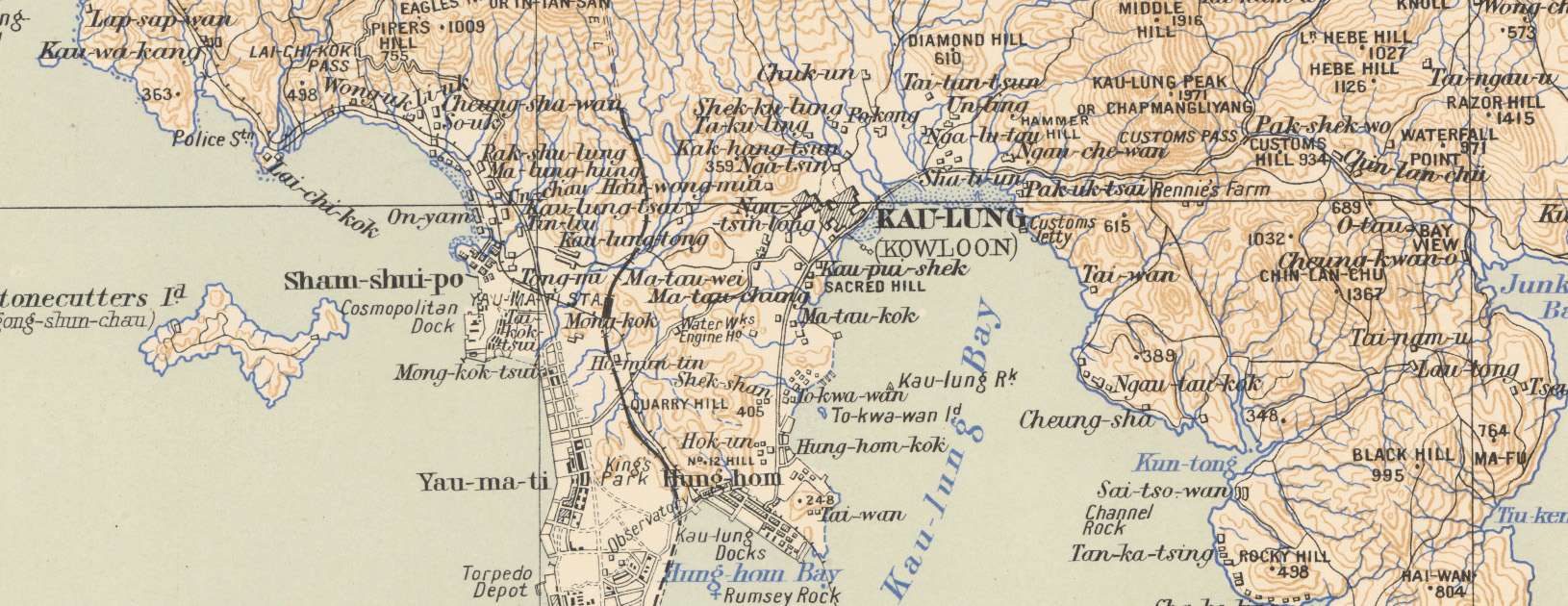

In Mong Kok, Nullah Road and Cheung Wong Road cut diagonally from northeast to southwest across an otherwise rectilinear street grid. It was built in the 1920s on what was then newly reclaimed land to carry a stream that flowed through Kowloon Tong to the Yau Ma Tei Typhoon Shelter. While it is now fully subterranean, there are plenty of hints to its existence: “missing” corners to certain buildings at the Prince Edward Flower Market, the long and narrow playground of the SKH Kei Wing Primary School on Lai Chi Kok Road, and the triangular electrical substation at Mong Kok Road Playground.

Even in new towns, street layouts were shaped by water engineering. There were once three streams that flowed into the bay of Tsuen Wan. When it was reclaimed for development in the 1960s, the largest stream was sent down a wide nullah at Tai Chung Road (“Big Stream Road”), which was eventually covered in the 1980s. The second stream was intercepted into a drain under Tai Ho Road (“Big River Road”), which despite its name, never carried open water. The third was sent under Kwan Mun Hau Street/Luen Yan Street. The two underground channels create the only strong diagonal lines in Tsuen Wan’s street network, providing the water with the most direct path to the sea.

There is probably an underground waterway in your own neighbourhood. Look at this map of the Drainage Services Department’s box culverts and trace them uphill; you will most likely find a natural stream. Subterranean streams are by no means unique to Hong Kong; urban development drastically alters the natural landscape. In London, the River Fleet was channelled into a sewer as early as the mid-19th Century. In Seoul, the Cheonggyecheon was paved over in the 1950s and turned into an elevated expressway in the 1970s, before being restored in the early 2000s.

From natural streams to artificial nullahs

In Hong Kong, the British started to dramatically alter Hong Kong’s hydrology almost as soon as they arrived, to serve the needs of a rapidly growing settlement. Streams were repurposed as drains and sewers and channelized to control floods. Disease prevention was another major motivation.

The first stream to be channelized was Wong Nai Chung (“Yellow Mud Stream”). Its reliable flow made its marshy valley a good place for rice farming, but for the early British settlers, it was a place of death and disease. In the early 1840s, up to half of all British troops were either killed or rendered unfit to serve by malaria. Western medicine had not yet figured out how malaria spread, but living near wet ground seemed to make people sick.

In the 1850s, Wong Nai Chung was channelized to drain the marshland and build the Happy Valley Racecourse. The lower reaches of the straightened stream was called Bowrington’s Canal after Governor John Bowring in English, or Ngo Keng (“the Goose Neck”) in Chinese. Today, people still call the Canal Road Flyover Ngo Keng Kiu (Goose Neck Bridge) even though this originally referred to a low bridge over the canal.

The role of mosquitoes in malaria transmission was discovered in 1897, which led to a renewed push over the next two and a half decades to “train” urban streams to eliminate the stagnant pools and vegetation in which mosquitoes bred.

Reclamation also required the construction of many nullahs. As the coastline extended outwards, it was necessary to dig drains to carry streams to the sea. For example, the Kai Tak Nullah north of Prince Edward Road East was once a natural stream, but south of the road on reclaimed land, it has always been an artificial channel.

From open nullahs to underground drains

The next stage in the disappearance of Hong Kong’s streams was the covering or “decking” of open nullahs. While some were covered as early as the 1920s due to traffic congestion, worsening water quality due to rapid urbanization in the post-war era provided even more impetus. In the early 1950s, Legco members began to complain about the “stench which rises to high heaven from the nullah at Kai Tak”.

Sources of water pollution were varied and location-dependent. The growth of paved urban areas generated more dirty surface run-off. Buildings erroneously connected their sewage pipes to stormwater drains. At Kai Tak, industrial effluents turned the water strange colours. Squatter villages such as those at Tai Hang and Diamond Hill, lacking in any sort of infrastructure, simply dumped their raw sewage into waterways. Pig farm waste was also a problem in rural areas and on the urban fringes until livestock farming was regulated in the 1980s.

The situation was worsened by the government’s longstanding efforts to capture as much water as possible in reservoirs, leaving little water to flow downstream and dilute the pollution (the environmental consequences of water capture will be further explored in part 2 of this series).

Modernity also generated increasing amounts of rubbish that was dumped or washed into waterways. In the 1980s, municipal workers fished 100 baskets of rubbish out of the Kai Tak Nullah daily. A few years prior in 1977, members of the government’s Keep Hong Kong Clean Campaign Committee discussed a pilot programme to fence a nullah near Tai Hang Tung Estate to keep rubbish out. But the committee found that people were still dropping rubbish out of high-rise windows into it, so some members proposed building a cage over the top. The Public Works Department rejected this on the grounds that it would be too expensive to build and maintain; maintenance workers would have to climb the cage to clean it. Moreover, children would be tempted to climb it, leading to injury. The conclusion was that the nullah should be decked. By the late 1980s, the majority of urban nullahs were covered.

As for the Bowrington/Goose Neck Canal, it was covered in the 1970s during the construction of the Canal Road Flyover. Today, the last open stretch of the Wong Nai Chung stream is found in the hills above Happy Valley, opposite Marymount Primary School. A tiny brook even during the rainy season, it trickles its way down some rocks and around a concrete pillar, before disappearing into a box culvert underneath Tai Hang Road.

Can lost streams be rediscovered?

While urban waterways were buried for good reasons at the time, the Drainage Services Department no longer recommends it. It says that covered nullahs are less effective at flood relief as water cannot flow in from either side, and that they are harder to maintain and monitor. Moreover, water quality has improved significantly since the 1980s even though it is still not safe to swim in. If pollution cannot be effectively controlled at the source, the DSD’s engineers can divert dirty water into the sewage system during the dry season.

In the last 30 years, there has been a global movement to “daylight” buried waterways by digging them up and restoring them to a natural or semi-natural state. The poster child for this was Cheonggyecheon, where Seoul’s government tore down the entire expressway and uncovered the stream as part of a massive urban regeneration project in 2003-05. These ideas have made their way to Hong Kong, with ambitious government projects to revitalize urban waterways such as the Kai Tak Nullah (since rebranded the Kai Tak River) and the Tsui Ping River (formerly known as the King Yip Street Nullah) in East Kowloon. However, it is debatable whether these principles have been applied appropriately to the Hong Kong context, or whether it is even possible to meaningfully restore biodiversity to long dead or wholly artificial waterways.

In part 2 of this series, we will explore the devastating impact of Hong Kong’s long history of engineering-based water management on its river ecosystems, what can be done to repair them, and the many challenges to restoring healthy river basins.

Sources:

Charles Terry (Legislative Council Member), Legislative Council meeting, 19 March 1952, Hong Kong Hansard.

David Dudgeon, “Anthropogenic Influences on Hong Kong Streams”, GeoJournal, v.40, 1996, pp. 53–61.

Drainage Services Department, “Stormwater drainage manual: planning, design and management, fifth edition”, January 2018,

Frederick Lugard (Governor), “Hongkong Roads and Nullahs”, Legislative Council meeting, 19 October 1911, Hong Kong Hansard.

JC-Wise Water Initiative on Sustainability and Engagement, Rivers@HK Database, 2024.

https://www.jcwise.hk/gis/index.php?lang=zh

In-keun Lee, “Cheong Gye Cheon Restoration Project”, Seoul Metropolitan Government, presented at Local Governments for Sustainability World Congress, 2006.

Ria Sinha, “Fatal Island: Malaria in Hong Kong”, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society Hong Kong Branch, Vol. 58, 2018, pp. 55-80.

Urban Council, “Memorandum for Members of The ”Keep Hong Kong Clean” Campaign Committee of The Urban Council”, USD/CO/11/528, 13 December 1977.

Urban Council, “The meeting of The Environmental Hygiene Select Committee of Urban Council”, USD ENH(K) 105/48, 3 September 1986.