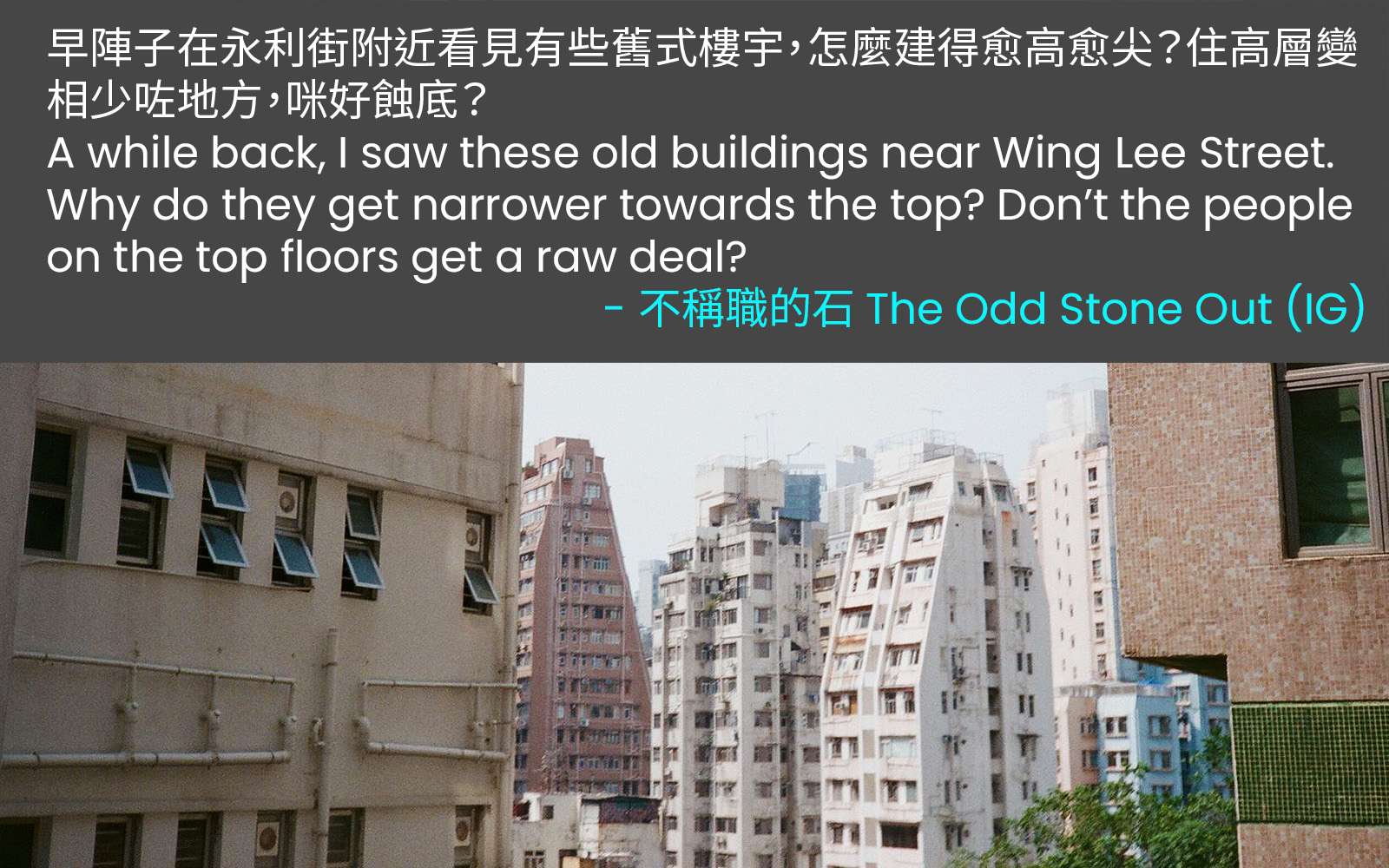

Why do some old buildings get narrower on top?

Reader questions answered

From 1969 to 1987, Hong Kong had something called the “street shadow rule”, which was intended to ensure that streets received adequate sunlight. Above a certain height, towers were slanted back at a 76 degree angle, creating a laddered or triangular profile. While the most typical sloped buildings were built during this period, various versions of the street shadow rule have existed since 1903, though it was not yet named as such. It originated in 19th Century regulations from England which aimed to improve living conditions in overcrowded and disease-ridden cities. One major method of doing so was by controlling the height of buildings in relation to the width of the street to ensure that they had enough sunlight and natural ventilation.

Early buildings regulations and the “shaving clause angle”

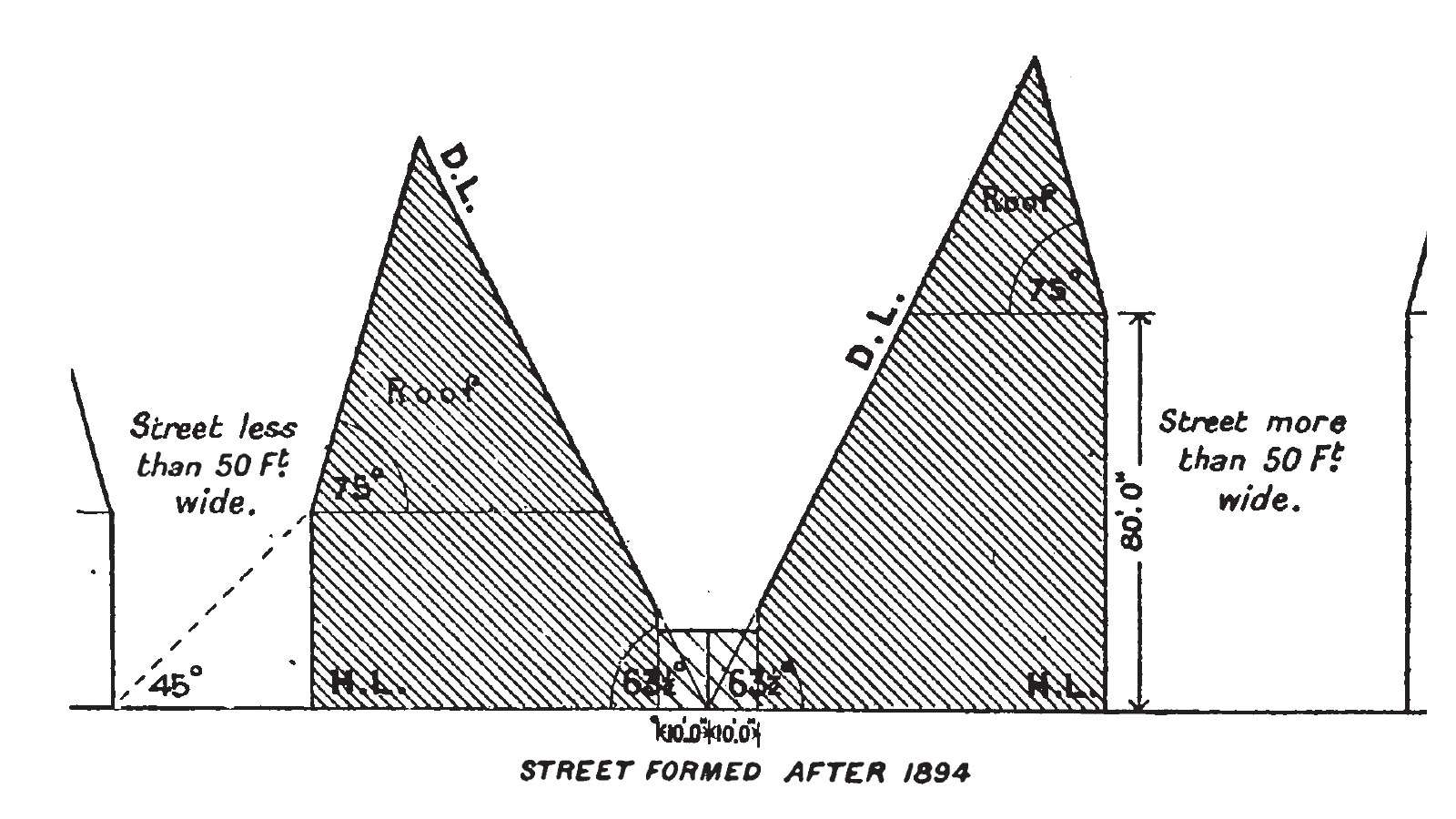

The ancestor of Hong Kong’s regulations was the London Building Act of 1894. In addition to defining the ratio of building height to street width, this law introduced the “shaving clause angle”, in which building masses were set back at specified angles–75 degrees in the front and 63.5 degrees in the back–to preserve sunlight.

These angles had no actual relationship to the sun’s position, but appear to have been a compromise between public health reformers who advocated for 45 degrees, and real estate developers who did not want to lose too much floor space. Regardless, similar angles would appear in Hong Kong’s building regulations for the next century.

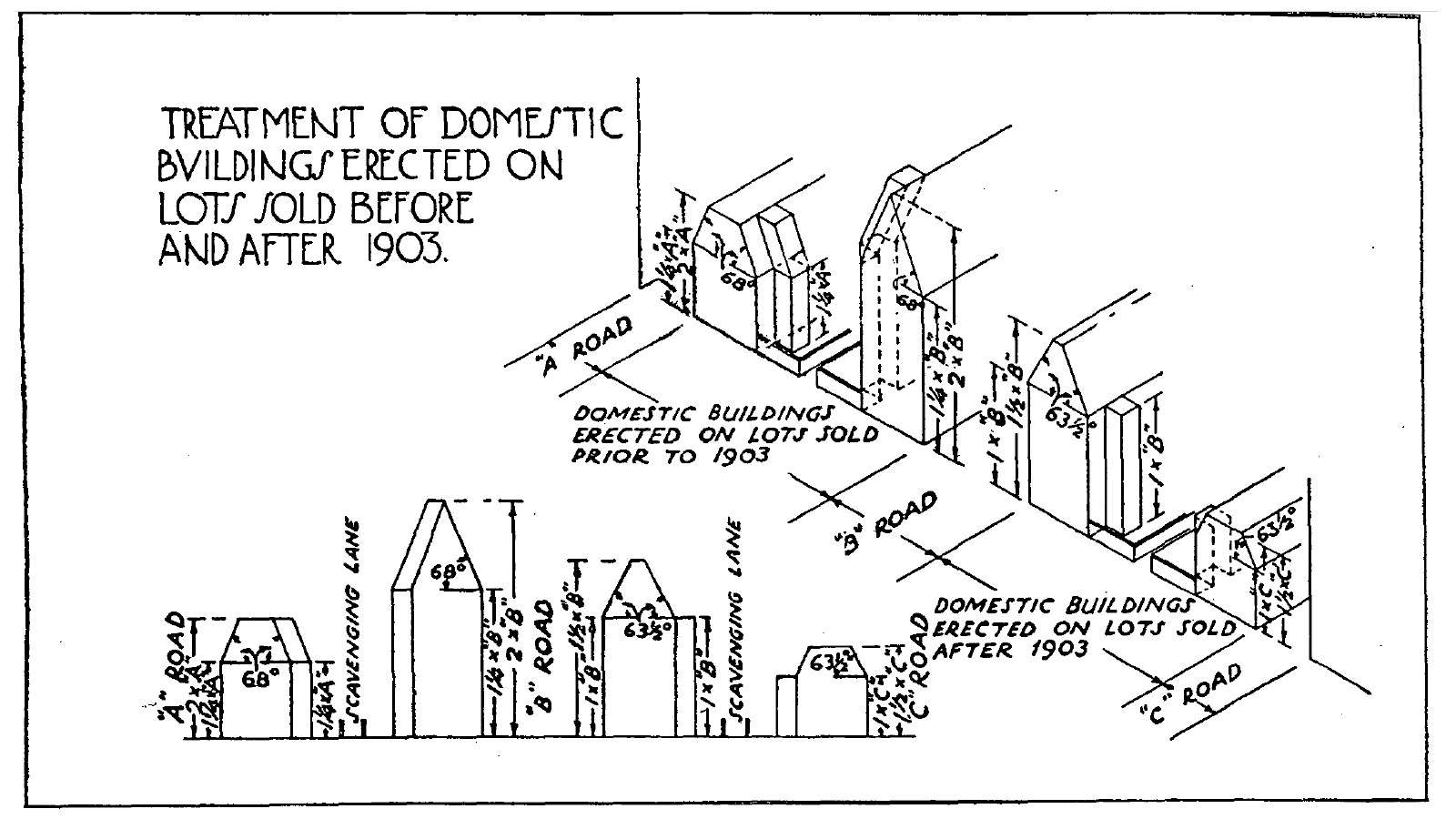

Hong Kong’s first building regulations, the Public Health and Buildings Ordinance of 1903, were passed after the bubonic plague outbreak of 1894. They limited the height of a building’s front wall to between 1 and 1.5 times the width of the street. Above this height, the building had to fit within a line sloping back at an angle of 30 degrees. This created a subtle stepping effect—buildings were capped at 4 storeys, with the fourth floor set back from the street.

The next iteration was the Buildings Ordinance of 1935. This limited the front wall to just 1 to 1.25 times the street width, above which buildings were to be angled back at 63.5 degrees (or 68 degrees for older lots) in both front and back, reaching a maximum height of no more than twice the street width. There are clear similarities between the diagram below from 1935, and the one above from London.

Most buildings were not angled in this way because they were only three storeys high, which was not much taller than the width of most streets. By law, anything exceeding three storeys had to be made of fireproof materials, which increased construction costs. No domestic building could be over 5 storeys without the permission of the Governor. One rare example that displays a 68 degree angle is the old Bank of China Building, which was built in 1950.

However, another rule within the Ordinance gave some five storey buildings a tapered appearance. Balconies had to fit within a 75 degree angle drawn from the ground to a point on the wall at a height equivalent to the width of the street. Therefore, the higher the floor, the shallower the balcony.

Bigger and boxier: the Buildings Ordinance of 1956-1962

As refugees streamed into Hong Kong after World War II, Hong Kong’s population grew from an estimated 600,000 1945 to 2.2 million by 1950. To address the severe housing shortage, the 1956 Buildings Ordinance introduced new regulations that greatly increased allowable building densities. These regulations created the extant cityscape of Hong Kong’s older districts, from modest six storey walk-ups to the massive Yick Cheong “Monster” Building of Quarry Bay. Under these rules, a building’s front wall could be twice the width of the street before sloping back at a 76 degree angle (slightly more than the 1935 balcony rule).

Instead of a simple height limit, density was now based on building volume, where the maximum volume equalled the site area, times the street width, times a “Factor” which was a multiplier of between 1.25 and 2.25 depending on the use of the building and how many streets the site abutted. Extra height and larger volumes were permitted on corner sites where buildings could receive sunlight from two or more sides.

For small sites facing only one street, the volume that could be gained by sloping back was often too insignificant to be worthwhile. However, if you pay close attention, you can sometimes spot subtle set-backs on the top two or three floors of 1950s and 60s tong laus, especially around the narrow streets of Sheung Wan.

Clearer examples of tapered buildings can be found on large corner lots. Hoi To Court in Causeway Bay, pictured below, follows a sample diagram from the 1956 regulations almost exactly. One half of the building steps back above the seventh floor, while the other half only starts stepping back above the 15th floor, taking advantage of the extra height permitted on corners.

Plot ratio controls and the building frenzy of 1962-1965

Within a few years, it became clear that the 1956 regulations were creating enormously bulky composite buildings like Mirador Mansion (1959) and Chungking Mansions (1961). The units inside were long and narrow, with few windows and little natural light. Therefore in 1962, the government overhauled the Buildings Ordinance, moving from controls based on volume to ones based on plot ratio. Plot ratio is a building’s total floor space divided by the site area, so a plot ratio of 10 means that a building has 10 times the floor space of the site.

These rules, which are still in place today, encourage tall slim buildings instead of squat bulky ones. A podium was permitted to cover an entire site up to a height of 15m (49 feet), above which one or more towers could emerge. The narrower the towers, the taller they could be.

The change took about a decade to materialize—the government granted a grace period of 3 years, so from 1962 to 65, landlords who realized that the new rules would reduce their sites’ development potential frantically submitted redevelopment plans. Among these rushed projects were the eight massive trapezoidal blocks of Man Wah Sun Chuen in Jordan. The building frenzy ended in an economic crash exacerbated by the riots of 1967. Many construction projects were cancelled or put on hold, so many older style buildings were not completed until the late 1960s or 1970s.

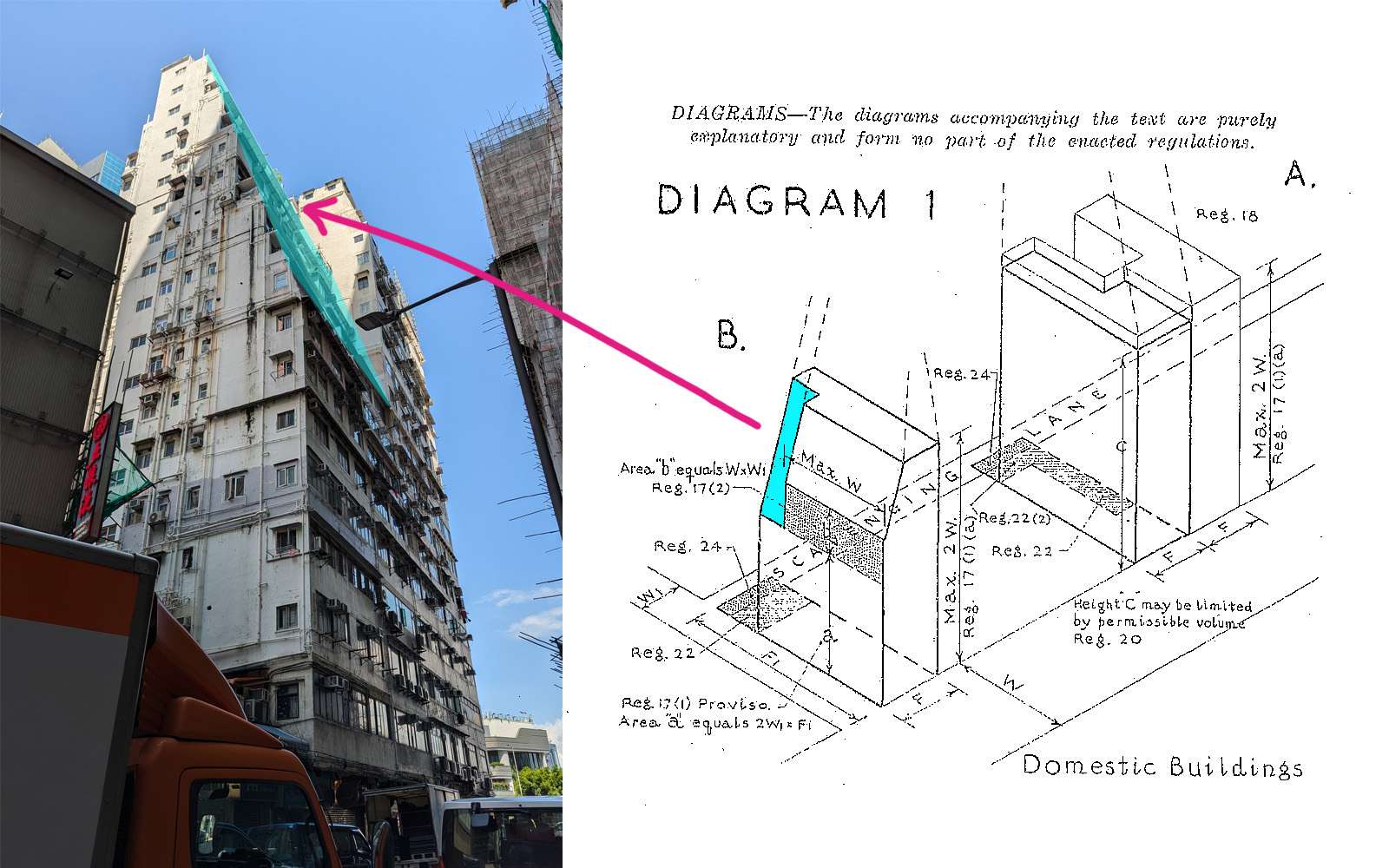

The Street Shadow Rule of 1969-1987

In 1969, the government reintroduced a new version of the street shadow rule. To accommodate the new plot-ratio based building forms, the 76-degree angled line started not from a point on the wall, but from an imaginary point in the centre of the road. Buildings on either side had to fit under this line, though corner sites were once again granted bonus height. Since towers were now taller and narrower, this version created the most dramatically tapered buildings.

The street shadow rule lasted until 1987. Some complained about it on aesthetic grounds, but mainly it was unpopular with developers because it restricted developable floor area and produced smaller units on higher floors. Ambiguities in the way the street shadow was calculated generated disputes and sometimes led to lawsuits. The rule was also a building safety hazard because the multiple ledges were a magnet for illegal structures.

And so after 86 years, an arbitrary angle from England disappeared from Hong Kong’s regulatory landscape. The government moved on to newer methods of controlling building densities through the statutory town planning system. Still, sunlight and ventilation remained relevant problems into the 21st Century. In the mid-2000s, the construction of large luxury waterfront developments provoked debates about the “wall effect” blocking breezes to surrounding neighbourhoods, pushing the government to develop new air ventilation assessment guidelines. The SARS and COVID-19 outbreaks raised alarm about inadequate ventilation in high-density housing. The Victorians’ solution may have been rather odd, but they were not completely wrong.

Sources:

Special thanks to Li Junwei, Ph.D student at the School of Architecture at the Chinese University of Hong Kong for answering our questions.

Bernard Dicksee, The London Building Acts 1894 to 1905, London: Edward Standford, 1906.

Roger Henley Harper, The Evolution of the English Building Regulations, 1840-1914, Vol. II, Ph.D Thesis, Faculty of Architecture, University of Sheffield, 1978.

Francisco García Moro, “The Death and Life of Hong Kong’s Illegal Facades”, Arena Journal of Architectural Research, July 2020, v.5 i.1.

Eunice Seng, “The City in a Building: a brief social history of urban Hong Kong”, Studies in History and Theory of Architecture, 2015, v. 5, p. 81-98.

Hendrik Tieben et al., “Environmental Urban Design and Planning Rules and their Impact on Street Spaces in Hong Kong and Macau”, presented at the 8th Conference of the International Forum on Urbanism, 2015.

C. Richard Wong, “Building Codes and Postwar Reconstruction in Hong Kong”, Hong Kong Economic Journal, 20 May 2015.

Wong Wah Sang and Yeung Tse Ngok, Handbook on Building Control in Hong Kong, USA: Scientific Research Publishing Inc., 2020.

Charlie Q. L. Xue, “Chapter 4: Government Control, Building Regulations and Their Implications”, in Hong Kong Architecture 1945-2015: From Colonial to Global, Singapore: Springer, 2016.

Han Zhou and Charlie Q. L. Xue, “Shaping the City with an Intangible Hand-A Review of the Building Control System in Hong Kong”, working paper, City University of Hong Kong 2014.