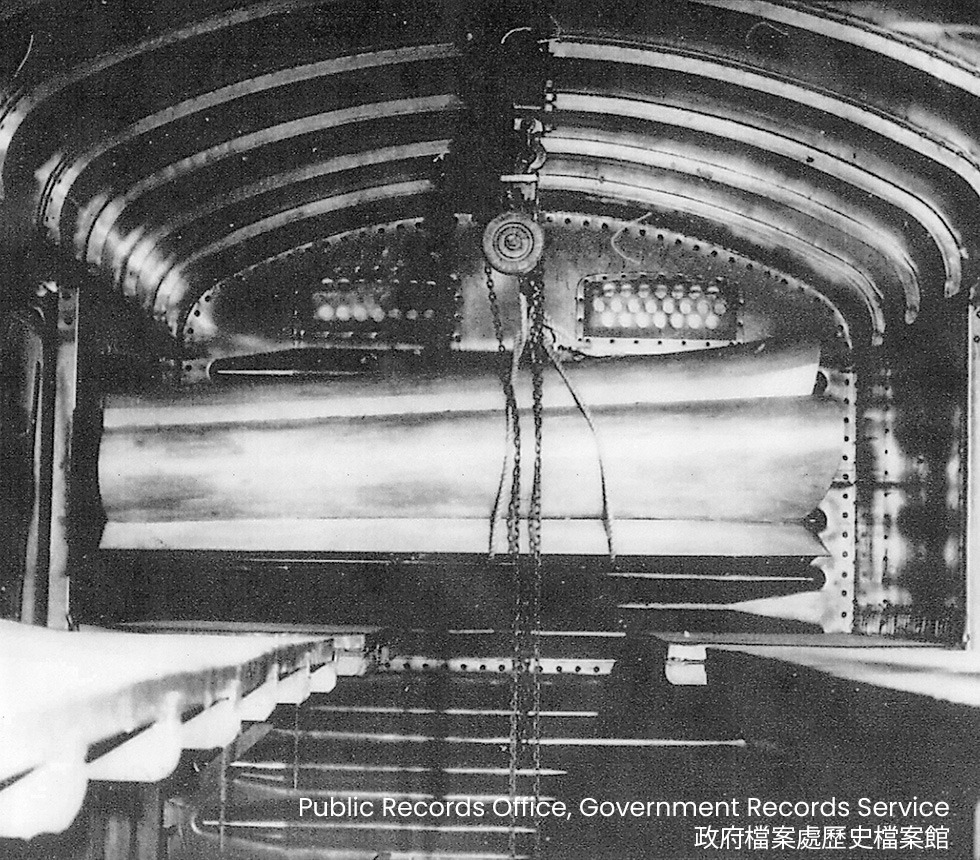

Inside of a coffin wagon specially designed for the Wo Hop Shek Branch Line

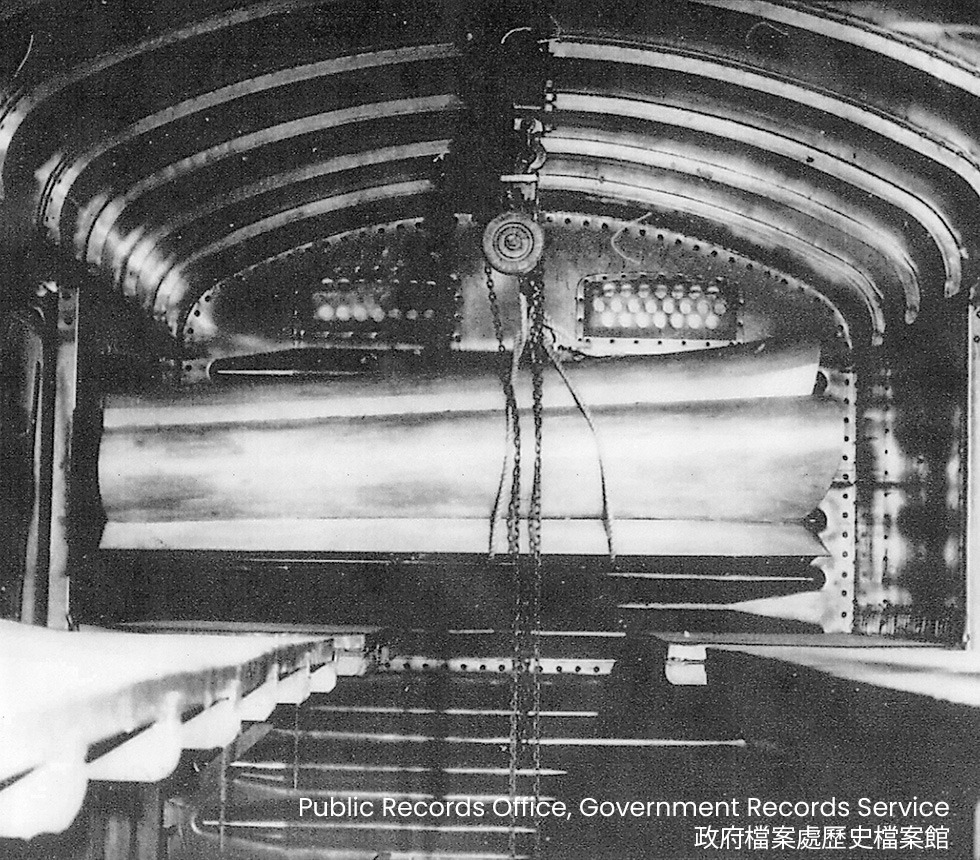

Inside of a coffin wagon specially designed for the Wo Hop Shek Branch Line

In the 1950s, 80% of Hong Kongers made their final journey by rail...

In 1950, I. B. Trevor, the general manager of the Kowloon-Canton Railway (KCR) wrote, “The world, as we know it, has infinite variety, and it would seem the Hong Kong Government has added one more…” It had built a railway for the dead.

From 1950 to 1983, the Wo Hop Shek Branch Line carried bodies from Hung Hom station to Wo Hop Shek Cemetery in Fanling. A roughly 950m branch off the East Rail Line carried hearse trains directly to the cemetery’s entrance. Train cars were specially modified to carry coffins, stacked two high. A steel I-beam ran the length of the ceiling, to which a pulley and chain were attached, allowing coffins to be lifted onto the upper shelves. Floor rollers near the doors helped workers slide the coffins in and out more quickly.

At Hung Hom Station, the KCR (then fully owned by the government) built a depot to receive the dead bodies, and a farewell pavilion (called 永別亭) for funeral ceremonies. Corpses from Hong Kong Island were first transported to Hung Hom by boat, and then by train to Wo Hop Shek. This was an entire logistics chain for managing death, something that all cities must do. The story of its construction and operation tells us a lot about the collision of land pressures, colonial administration, and cultural practices.

In 1937, the colonial government started planning a huge new cemetery in Fanling. Urban cemeteries were filling up, and urban land was considered too valuable to keep allocating it to the dead. The distance made a dedicated railway the most cost-effective transportation solution. Neither the Lion Rock Tunnel nor the Fanling Highway had been built yet, and the journey by road from Kowloon was slow and expensive. Moreover, in logistics, the “last mile problem”- travelling from a transportation hub to the final destination – is often the most costly part of the journey. Therefore, instead of delivering bodies to Fanling Station by train, and then to the cemetery by lorry, it made sense to build a track right up to the cemetery’s entrance. Railway hearses existed in parts of Europe and Australia, so it was not a totally novel concept. Construction was interrupted by the Japanese invasion in 1941, but the project was finally completed in 1950.

The decision to build Wo Hop Shek Cemetery was not a popular one. It was meant to replace all public urban cemeteries and many of the private ones. Not only would they stop accepting new burials, some would be closed down, the graves exhumed, and the remains relocated to Wo Hop Shek. The Tung Wah Group, which provided social services for the Chinese population on a charitable basis, objected as their cemeteries were slated for closure.

In fact the periodic removal of Chinese cemeteries by the government had been a sore spot since early colonial days. This was an inconvenience the colonial government exempted Europeans from, as the Hong Kong Cemetery in Happy Valley where non-Chinese Protestants were buried since 1845 was allowed to stay open.

In 1947, anticipating Wo Hop Shek’s unpopularity, the government inspector for cemeteries S. F. Warburton recommended that Aberdeen and Ap Lei Chau Cemeteries, which were permitted to operate a few years longer, should only accept residents who died in the same district. Otherwise, people would fake their home addresses. “Trickery will come into operation,” he wrote. He also suggested that only lifelong Catholics be interred at the private Catholic cemetery to discourage late life conversions to secure a burial plot. Europeans would be exempted.

To try to defuse public opposition, the government offered to transport coffins to Wo Hop Shek for free and offered each family up to six discounted train tickets to accompany the coffin. In 1950, citing the long journey, residents of Aberdeen and Ap Lei Chau petitioned the government for permission to build a new cemetery on Ap Lei Chau. The government rejected it. Instead, starting from the Chung Yeung Festival in 1951, they offered a 1/3 discount on train fares to Wo Hop Shek during the grave sweeping festivals. Despite these concessions, in the late 1950s, less than half of all coffins were accompanied to Wo Hop Shek by relatives. Most people held funerals at the farewell pavilion in Hung Hom, then left the bodies in the care of Urban Services Department workers.

On grave sweeping festival days, the KCR ran 10-13 special trains per day from Tsim Sha Tsui and Yau Ma Tei Stations to Wo Hop Shek and Sandy Ridge (an urn cemetery at Lo Wu). Special buses were arranged between Fanling Station and Wo Hop Shek cemetery. By 1958, the crowds had become so large and unmanageable that the Police asked the KCR to erect steel crowd control barriers at Wo Hop Shek Station. In 1968, an Urban Council memo noted that the policy of concentrating all burials at Wo Hop Shek had created “difficult problems of crowd control and traffic at the Ching Ming and Chung Yeung Festivals”. Unlicensed minibuses engaged in price gouging. As private cars became increasingly popular, the government banned driving into the cemetery on festival days. Hong Kong’s twice yearly tradition of day-long family outings to Fanling accompanied by traffic mayhem was created by a planning decision.

The Wo Hop Shek Branch Line continued to operate until after the Ching Ming Festival in 1983, when the KCR switched from diesel to electrified trains. By then, demand for the service had declined. The completion of the Lion Rock Tunnel in 1967 reduced journey times to the New Territories by road. Demand for coffin burials also declined; to save on cemetery space, the government aggressively promoted cremation, and Hong Kong’s cremation rate rose from 2% in 1960 to 57% in 1982 (that figure is now over 90%). Moreover, by the 1980s, social customs were changing and fewer people visited graves on Chung Yeung. In its final year of operation, the special Ching Ming train departed Hung Hom only once every 2 hours. For the KCR, it no longer made sense to keep a track for which there was declining need, but cost $150,000 annually to maintain. Today, the branch line is gone, dismantled to make way for housing developments in Fanling South. The problem of where Hong Kong can find the space to put the dead, however, remains.

Sources:

I.B. Trevor, “Carriage of Coffins by Railway from the Urban to the Country District for Burial,” Kowloon-Canton Railway 1950, HKRS 48-1-190 General Correspondence Files, HKSAR Public Records Office.

S. F. Warburton, “Wo Hop Shek Cemetery”, Inspector of Cemeteries, Hong Kong Government 1947, HKRS 48-1-190 General Correspondence Files, HKSAR Public Records Office.

Wong Wing Yin, “Crowd Control–Wo Hop Shek”, Memo from Commissioner of Police to Director of Public Works, 1958, HKRS 48-1-191 General Correspondence Files, HKSAR Public Records Office.

Government Secretariat, “Cheap Return Fares on the Railway – Arrangement for…to Wo Hop shek and Sandy Ridge at the Two Grave Worshipping Festivals Each Year”, 1951, HKRS41-1 Files Relating to General Administration of the Colonial / Government Secretariat, HKSAR Public Records Office.

Ko Tim-keung, “A Review of Development of Cemeteries in Hong Kong: 1841-1950”, Journal of the Hong Kong Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, Vol. 41 (2001), pp. 241-280.

Chan Yuk-wah, “Management of Death in Hong Kong”, MPhil thesis, Chinese University of Hong Kong, 2000.

〈 關和合石墳場:港府志在必行〉(“On Wo Hop Shek Cemetery, Hong Kong Government is determined to proceed”), 天光報 (Tien Kwong Morning News), 15 November 1940.

〈九廣路代運棺材,每具百五元〉(“Kowloon-Canton Railway ships coffins, $150 a piece”), 香港工商日報 (Hong Kong Kung Sheung Daily News), 12 September, 1950.

〈加班往和合石〉(“Special train service to Wo Hop Shek”), 華僑日報 (Overseas Chinese Daily News), 3 April 1983.

〈和合石鐵路支線明起停止服務,將成歷史陳蹟〉(“Wo Hop Shek Branch Line ends service from tomorrow, will become a trace of history”), 工商晚報 (Kung Sheung Evening News), 10 April 1983.

Tymon, “Wo Hop Shek Spur Line”, Industrial History of Hong Kong Group, 2 September 2023.