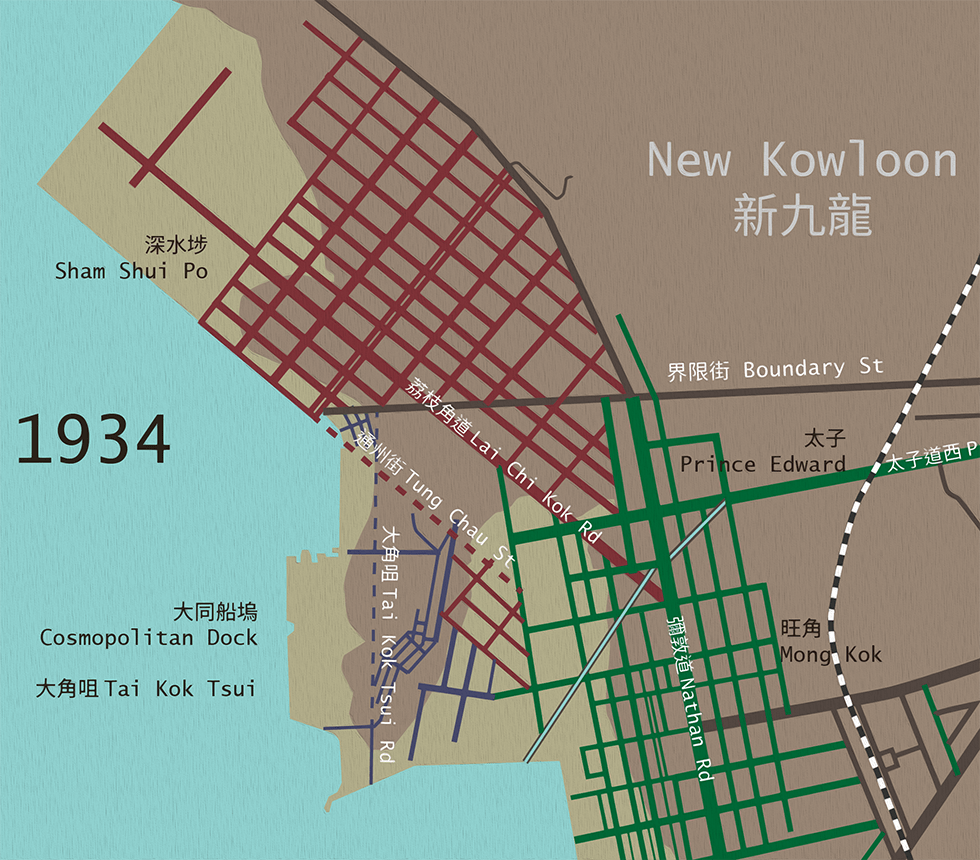

Map of street networks of Sham Shui Po, Tai Kok Tsui, Mong Kok and Prince Edward in 1934

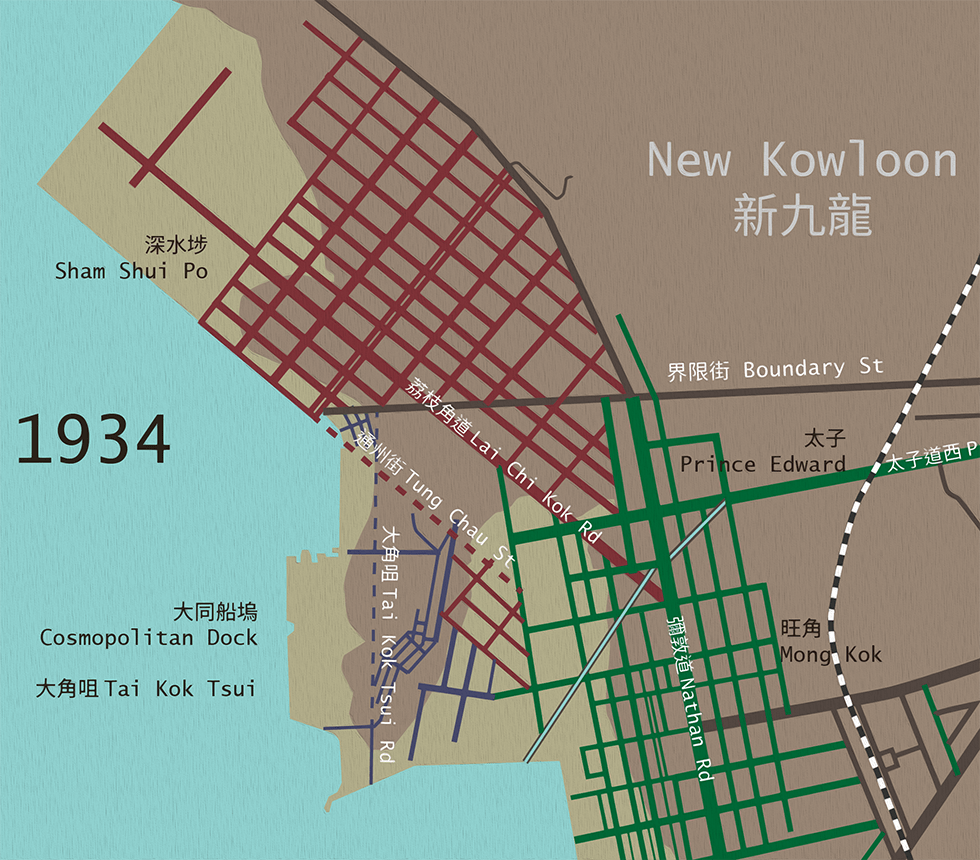

Map of street networks of Sham Shui Po, Tai Kok Tsui, Mong Kok and Prince Edward in 1934

When three neighbourhoods met up for the first time

In Part 1 of this series, we explored the many leftover triangles of Prince Edward—triangle buildings, triangle parks, and triangle traffic islands. Why are there so many triangles in Prince Edward? Where did they come from?

The short answer is that the street grid is oriented to the coastline. Between Jordan and Mong Kok, the street grid is oriented north-south parallel to Nathan Road. Around Prince Edward, the coastline starts to bend northwest towards Lai Chi Kok, and so does the street grid. Where the two grids intersect, triangles are formed.

The long answer is that the coastline of Kowloon is man-made, and therefore did not have to develop exactly in this way. Then there is Tai Kok Tsui, where there is a disorienting mish-mash of three different grid alignments. To explain how this happened, we need to look into the past.

In the 19th Century, Kowloon was mostly rural. As British military bases occupied much of Tsim Sha Tsui and Yau Ma Tei, urban development had to expand up a narrow strip of land on the western coast of the peninsula. The colonial government started selling waterfront plots to investors in the 1870s, who reclaimed land up to Ferry Street by the early 1900s. (In those days, reclamation was privately funded – the government actually auctioned pieces of coastal seabed.) This established the roughly north-south street grid of Yau Ma Tei and Mong Kok. Old districts in Hong Kong are usually gridded wherever flat land was available as grids made land administration and rapid expansion convenient.

North of Mong Kok, there was still little urban development. The Cosmopolitan Dock, a large scale ship repair facility and oil depot, had been built on the peninsula of Tai Kok Tsui right near the border with Qing China in 1875. There were a few rows of housing on the opposite side of the peninsula, but Tai Kok Tsui was still separated from Mong Kok by the bay, and from Sham Shui Po by small hills. Over time, the bay would be reclaimed and the hills flattened for building material.

Sham Shui Po was a Hakka village that lay just north of the boundary line. When the British acquired the 99-year lease on the New Territories at the Second Convention of Peking in 1898, this land skyrocketed in value. Wealthy Chinese investors, chief among a prominent building contractor named Li Ping, bought up the surrounding farmland in anticipation of profit.

Between 1903 and 1920, the government resumed Sham Shui Po Village and started reclamation. Li Ping and other landowners were offered large lots in compensation, enabling them to develop Sham Shui Po into a modern industrial town with good quality tong lau. These were meant to be a major upgrade from the shoddy, unhygienic housing available to Chinese workers elsewhere in the city. The Acting Governor at the time, Claud Severn, was so impressed that he called them “practically rat-proof”. The new town was laid out in a grid bounded by Nam Cheong Street, Yen Chow Street, Tung Chau Street and Apliu Street on a northeast-southwest alignment like the old village, which would allow expansion into the bay of Cheung Sha Wan with further reclamation.

In 1924 there were still three mostly disconnected grids, the north-south Mong Kok grid, the northwest-southeast Sham Shui Po grid, and the beginnings of Tai Kok Tsui’s grid which was angled slightly differently to Mong Kok’s. In between them was farmland, or vacant recently reclaimed land.

The three grids were merged on paper a few years later. In 1922, having decided that Hong Kong had become large and strategically important enough to need a dedicated planning department, the colonial government formed the Town Planning Committee. Additionally, the development of Sham Shui Po had brought in so much land revenue that it fuelled an appetite for even more expansion into north Kowloon. So in 1926, they issued a long term planning scheme for Kowloon, marking out the major transportation corridors and drawing out areas for future reclamation and development.

The Sham Shui Po grid was extended southeast, colliding with the Mong Kok grid. After levelling the hills, the construction of Tung Chau Street and Tai Kok Tsui Road would connect Tai Kok Tsui with Sham Shui Po. Part of Tai Kok Tsui’s grid was rearranged parallel to Sham Shui Po’s to facilitate the alignment of a railway from Lai Chi Kok to Tsim Sha Tsui that was in the end not built. The old frontier line became Boundary Street, which travelled east-west at an angle that did not quite line up with either grid. By the 1930s, most of the gap in the middle had been filled in according to the plan, creating the leftover triangles so unique to Prince Edward.

Pui-yin Ho, Making Hong Kong: A History of Urban Development, Edward Elgar Publishing, 2018.

Cecilia L. Chu, Building Colonial Hong Kong: Speculative Development and Segregation in the City, Routledge, 2022.

Roger Bristow, Land-Use Planning in Hong Kong: History, Policies and Processes, Oxford University Press, 1984

HKSAR Marine Department, A brief history of the Hong Kong dockyards.

Map of the Hong Kong and of the territories leased to great britain under the convention between Great Britain and China signed at peking on the 9th of June, 1898, (1905) ( map no. 52* )

Kowloon and part of New Territories 1903 (Ordnance Survey Office, Southampton, 1904)

Kowloon and part of New Territories, surveyed in 1902-1903 under superintendence of Major H S King R E, corrected 1924.

Town Planning Schemes for Kowloon and New Kowloon, CO129/494, 1926.

Aerial photographs of Hong Kong, EAGLE/RN/HK/0001, Defence Geographic Centre, National Collection of Aerial Photography, Scotland, 1934.

All historical maps viewed at hkmaps.hk