Photo credit: Joshua Wolper, January 2024

Photo credit: Joshua Wolper, January 2024

An abandoned, hollowed out fire hydrant sits by an overgrown path in a forest. Its red paint, though faded and patchy, is incongruous against a backdrop of greens, greys and browns. Although it is only a few minutes’ walk from Lai Tak Tsuen, a public housing estate in Tai Hang, the forest feels dense and secluded, but all around is the debris of human habitation.

The ground is littered with loose tiles, vinyl flooring, broken glass, wrecked appliances, plastic flip-flops, discarded toys, and so many bottles—beer bottles, rice wine bottles, soda bottles with 1980s logos. Unnatural rectangular forms protrude from the slopes—cracked concrete platforms, partially demolished walls, building foundations and water tanks with plastic drainpipes still sticking out of them.

From the end of World War II until the early 1990s, the hills that overlooked Tai Hang Point were blanketed with what international development economists call “informal settlements” but which were then simply known as squatter areas. Squatter villages sprang up on the edges of the city as refugees streamed into Hong Kong in the 1950s, ‘60s, and ‘70s. The area above Tai Hang was one of the largest squatter areas on Hong Kong Island, with a population of 15,000 at its peak in the mid-1960s.

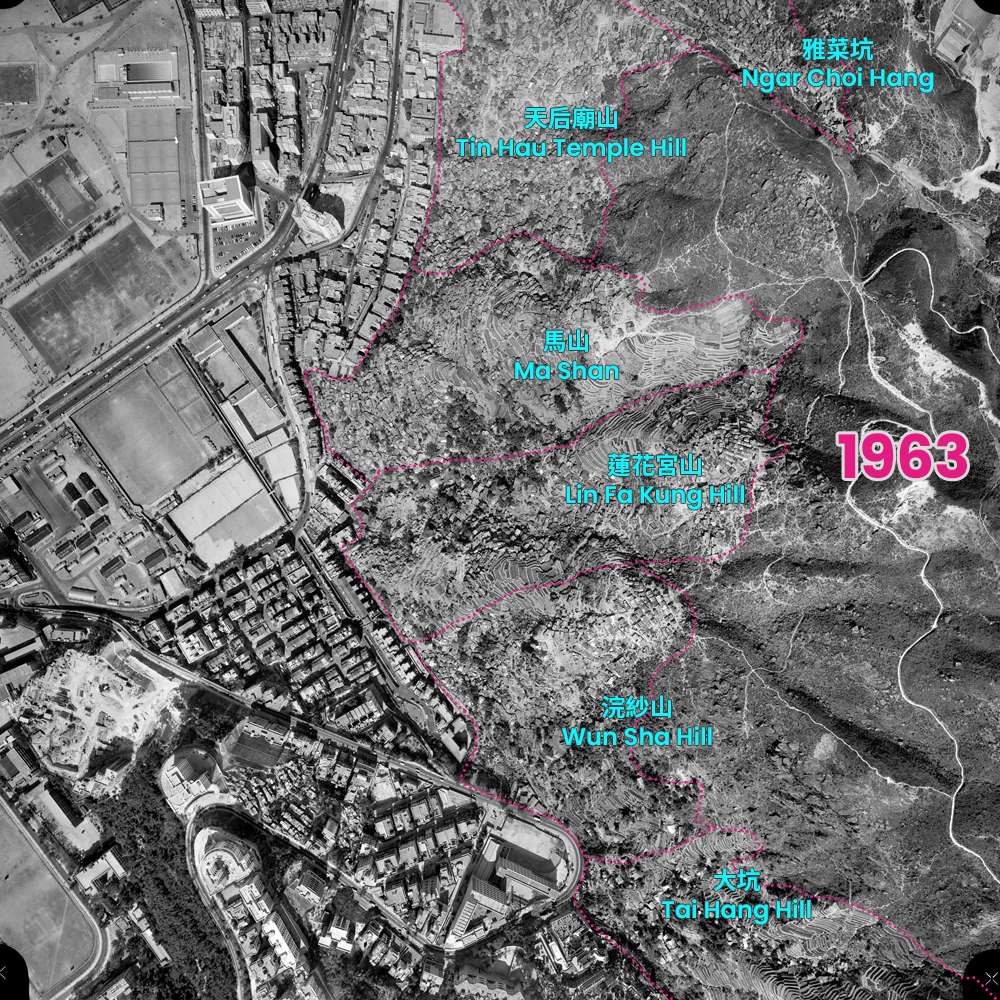

What appears to be an undifferentiated mass in aerial photographs was actually six separate village clusters, Ngar Choi Hang, Tin Hau Temple Hill, Ma Shan, Lin Fa Kung Hill, Wun Sha Hill and Tai Hang Hill. Each was formed around a network of steep paths winding up and down the slope. There were almost no lateral paths linking the villages together, noted a 1969 police memo complaining about how poor accessibility hindered night-time drug raids. It took police officers 10 or 15 minutes to run up each slope, enough time for drug dealers to get away.

What was it like to live there? In City Unseen’s first feature video, “Seeking Home: Tai Hang’s Vanished Villages”, we interview former resident Ng Tin Tak (who everyone calls Uncle Tak) who lived on Lin Fa Kung Hill as a boy in the 1950s. His parents built themselves a simple plywood and tin sheeting shack with a tar paper roof. Uncle Tak recalls seeing his neighbours’ roofs peeling clean off in typhoons. These cheap, light, and highly flammable materials were sold at the bottom of the hill. Fires were a frequent occurrence, and many villagers believed that some were started deliberately just to generate more business for the building materials dealers.

The 1963 aerial photo shows that instead of a forest, the hillside was wrapped in tiny, terraced fields. People tried to farm this improbable terrain, at least for a while. Later aerial photos show that the cultivated area had diminished by the early 1970s, though stone retaining walls can still be seen. Uncle Tak’s parents briefly tried to grow vegetables, but found it too much effort to be worthwhile. Their main source of income was raising pigs, a life of unrelenting hard work. Uncle Tak’s most positive childhood memories took place away from the village, when he escaped his chores to wander around Causeway Bay, or the time he ran downhill in the dark to watch the Tai Hang Fire Dragon Dance. It only took him 5 or 10 minutes, he was too young to be afraid.

There were no street lights back then, nor any other kind of public infrastructure. We also interviewed Alan Smart, Professor Emeritus of Anthropology at the University of Calgary, who has researched squatter settlements since the 1980s, about the colonial government’s policies. Up until the 1970s, they treated squatter areas with deliberate neglect for fear of encouraging more squatting. Where the government refused to provide services, the triads filled the gap. By the 1960s, triads were selling illegal hook-ups to electricity and water, and building huts for cash. They even offered customers money-back guarantees if government inspectors caught them before their huts were finished.

The unwritten policy was to demolish any new construction, but to tolerate pre-existing squatter huts. So huts were thrown up as quickly as possible, then residents would surreptitiously upgrade them from the inside, taking care to preserve an external layer of old plywood and metal sheeting to avoid detection. The remains of brick, tile and concrete scattered over the hillsides today were the product of years of stealth renovations.

But as much as government officials hoped that squatters would simply go away, this was never a realistic course of action. The costs of ignoring the problem proved too great. Watch the video to find out how government decisions changed the lives of residents like Uncle Tak, and how squatters ended up changing the entire course of Hong Kong’s urban development. Also check out our Facebook and Instagram pages for video out-takes and bonus photos.

Alan Smart, The Shek Kip Mei Myth: Squatters, Fires and Colonial Rule in Hong Kong, 1950-1963 (石硤尾神話:寮屋、火災和殖民統治下的香港,1950年至1963年), Hong Kong University Press, 2006.

Alan Smart and Fung Chi Keung Charles, Hong Kong Public and Squatter Housing: Geopolitics and Informality, 1963-85 (香港的公共房屋與寮屋:地緣政治與非正規化,一九六三至一九八五), Hong Kong University Press, 2023.

Alan Smart, “Agents of Eviction: The Squatter Control and Clearance Division of Hong Kong’s Housing Department”, Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography, v. 23 i. 3, 2002, pp. 333-347.

Ko Tim-keung, “Memories of a Bygone Era: Resettlement in Hong Kong 1950-1972”, exhibition brochure, Hong Kong Jockey Club University of Chicago Heritage Courtyard and Exhibition Centre, November 2020.

Hong Kong Memory, “Land Squatters”, hkmemory.hk, 2012.

Eastern District Office, “Conversion of usage of huts in Ngar Choi Hang Village as at 1982.6.1”, handwritten memo, Hong Kong Government, 1 June 1982, HKRS1443-5-9, Government Records Service, HKSAR Government.*

Author unknown, 大坑建廉租屋邨木屋居民將徙置石排灣咸田秀茂坪任擇, 20 January 1969, HKRS70-1-452-134, Government Records Service, HKSAR Government.*

Operations Branch, Housing Department, “Report on Squatter Area Improvements 1982”, 1982, HKRS 755-1-3, Government Records Service, HKSAR Government.*

Eastern District Office, “Re: Tai Hang District,” 17 November 1969, in “Problems in Tai Hang (Eastern District)”, HKRS413-4-16, Government Records Service, HKSAR Government*.

Working Party on Electrification of Squatter Areas, “Report of the Working Party on Electrification of Squatter Areas”, Hong Kong Government, 1975-81, HKRS 755-1-3, Government Records Service, HKSAR Government*.

J. C. McDouall (Social Welfare Officer), “Enclosure 1, Report on Squatters Dated 8.11.50 by S. W. O.,” 8 November 1950, HKRS 163-1-1231, Government Records Service, HKSAR Government*.

C. B. Burgess (Deputy Colonial Secretary), Memorandum to Colonial Secretary John Fearns Nicoll, 14 December 1949, HKRS 163-1-1231, Government Records Service, HKSAR Government*.

William James Gorman (Chief Officer, Fire Brigade), “Memorandum: Squatter Fire, Kowloon City & Existing Risk”, 12 January 1950, HKRS 163-1-1231, Government Records Service, HKSAR Government*.

Staff writer, “Squatters Mob Officials,” The China Mail, 9 April 1970.

Staff writer, “Reds Wooing Squatters,” The Star, 20 May 1970.

Government Records Service, “Squatter settlement above Tai Hang Road, 4 December 1963/ 大坑道附近山坡上的寮屋區, 攝於 1963 年 12 月 4 日,” (photo), Call No. 01-13-373, Government Records Service, HKSAR Government.*

Government Records Service, Shek Kip Mei Resettlement Estate (photos) in “Hawker Control–Hawker Control in Group B Estates”, 1967-79, HKRS309-1-5, Government Records Service, HKSAR Government.*

Government Records Service, “Wah Fu Estate (1968)”, (video) Ref No. 0016-E017, Government Records Service, HKSAR Government.*

Government Records Service, “An aerial view of the construction of On Ting Estate and Yau Oi Estate,” (photo) c.1970s, X1000188, Government Records Service, HKSAR Government.*

Government Records Service, “Tai Hing Estate”, (photo) 1980, 306.34095125 HON, Government Records Service, HKSAR Government.*

Government Records Service, panoramic photograph of Bayview hillside in “Bay View Hillside Squatter Areas–Proposed footpath to Facilitate Police Action Against Drug Activities in the…”, (photo) 1969/70, HKRS 156-2-4056, Government Records Service, HKSAR Government.*

Information Services Department, “Fire at Diamond Hill”, 3699-9, 12 July 1965, Information Services Department, HKSAR Government.

Information Services Department, “Standpipe”, 395-001, 1 June 1958, Information Services Department, HKSAR Government.

Survey and Mapping Office, Digital Orthophotos 63_7456 2 February 1963, 07026 12 February 1973, A03746 6 December 1985, CN18537 13 November 1997, CW83503 26 August 2009, Lands Department Open Data, HKSAR Government.

M.C. Tang, “Report on the Rainstorm of May 1982—Geo Report No. 25”, (plates 2 and 6), 1982, Civil Engineering and Development Department, Hong Kong Government.

Anonymous, “Lin Fa Kung Street West”, c.1950s, 歷史時空 Facebook Group.

Michael Rogge, “Hong Kong Squatters in 1962,” YouTube.

Michael Rogge, “Hong Kong squatter village fire 1953,” YouTube.

Ko Tim Keung, “Tai Hang Tung Squatter Fire,” 1954, Hong Kong Memory.

Ko Tim Keung, “Former squatter dwellers become homeless after a fire in Nga Choi Hang (North Point),” early 1950s, Hong Kong Memory.

Ko Tim Keung, “Tai Hang Squatter Area,” 1965, Hong Kong Memory.

Ko Tim Keung, “Tai Hang Squatter Area After Fire,” 1966, Hong Kong Memory.

Ko Tim Keung, “Sau Mau Ping Resettlement Estate,” 1968, Hong Kong Memory.

Ko Tim Keung, “Shek Pai Wan Resettlement Estate Under Construction,” 1966, Hong Kong Memory.

〈歡迎「代表」被阻于粉嶺〉 (photos), Kung Sheung Evening News, 2 March 1952.

〈九龍大街衝突事件被群眾焚燬至三架軍警及私家車〉 (photos), Kung Sheung Evening News, 2 March 1952.

“Street hawkers 路邊小販”, 1940s, FF-DBW-0955, Frank Fischbeck Collection, University of Hong Kong Libraries.

“Shek Kip Mei Fire 石硤尾大火”, 1953, FF-DBW-107, Frank Fischbeck Collection, University of Hong Kong Libraries.

“Governor Sir Murray MacLehose 港督麥理浩爵士”, 1970s, FF-DBW-1334, Frank Fischbeck Collection, University of Hong Kong Libraries.

“Plea for Homes” (photo), The Star, 20 January 1970.

“Give us more time to move” (photo), The Star, 15 October 1970.

“Dragged from home” (photo), The China Mail, 12 January 1970.

“Squalid squatter area & resettlement block” (photos), The Star, 26 April 1969.

“Resettlement workers silhouetted against the sky as they commence work,” (photo), South China Morning Post, 13 January 1970.

*For images that are provided by the Government Records Service. If you wish to use the images, you must submit application in writing to the Government Records Service.